By Terry Ward

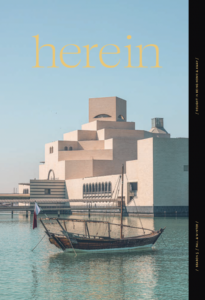

A chat with the director of the country’s Museu Nacional do Azulejo (National Tile Museum) reveals recent discoveries and sheds light on the very Portuguese love affair with the iconic tiles.

Strolling the streets of Lisbon, Porto and nearly any other city or town in Portugal, it’s impossible to miss a singular architectural feature–tiles, tiles, everywhere that are as much a part of the urban landscape as the country’s ubiquitous cafes selling the delicious custard tart called pastéis de nata.

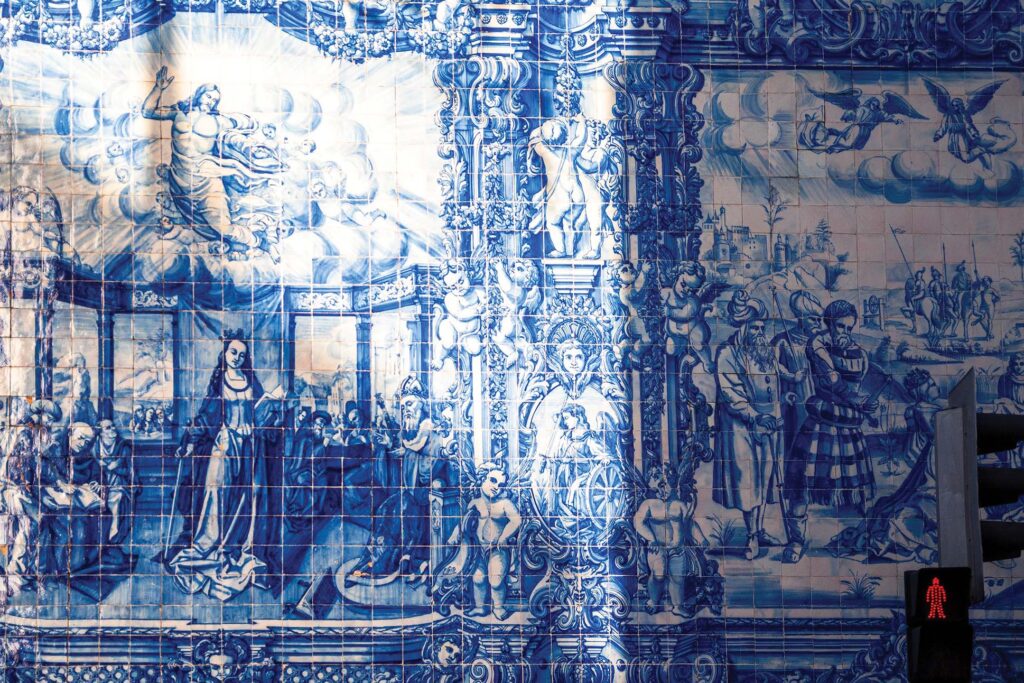

Called azulejos (from the Arabic word azzelij, which means “little polished stone”), the tiles were originally brought to Europe by invading Moors in the 13th century. But it wasn’t until the 16th century that the presence of azulejos in Portuguese architecture really exploded onto the scene. They’ve been an ever-evolving fixture in the country ever since, found everywhere from inside historic palaces and on the facades of churches and restaurants to decorating the walls of Lisbon’s subway system, considered among the most beautiful in the world, and even in modern day graffiti, too.

We sat down with the director of Lisbon’s Museu Nacional do Azulejo, Alexandre Pais, to learn more about the deep Portuguese relationship with azulejos and how their expression in art and architecture has evolved over the centuries.

HEREIN: Is there a particularly spectacular display of azulejos people might miss at the National Tile Museum that you can point us toward?

PAIS: You can’t miss the museum’s greatest jewel, the Grande Panorama de Lisboa, a representation of Lisbon in the 18th century. And you won’t, either, because it’s a very large panel stretching for 40 meters that shows how the city looked during this time period.

It’s a very important historical document of sorts for our country because Lisbon was destroyed in 1755 by a very damaging earthquake. In this panel of azulejos, you can see what was lost.

The depiction of the Royal Palace, right in the center of the panel, is so opulent. You see this panel and could think the Royal Palace was still standing in Lisbon today as it is in this depiction. But the palace was lost, along with its contents, during the earthquake and ensuing tsunami. It housed a very important collection of African, South American and Asian art since the kings of Portugal were always demanding that their ships making navigations bring back objects from those places. It was a very important structure but it all disappeared in the disaster. After you see this panel of azulejos you can walk to the area where the palace once stood in Lisbon, the Praça do Comércio, one of Europe’s biggest squares, and imagine the building as it once existed there.

There are some other surprises to discover in the museum, too. The Museu Nacional do Azulejo occupies the site of an ancient convent from the 16th century. When people come here they aren’t expecting to see parts of that ancient baroque building. I’ll save the details so you can visit yourself and be surprised by its splendor.

HEREIN: In Portugal, azulejos have been called a form of “identity art” for the country. Can you explain what that means?

PAIS: Through azulejos, you can understand who the Portuguese are as a people, how we react to history and all the demands that history makes on us, too. It’s a very rich way of understanding how the Portuguese behave and express themselves. The way azulejos are used in Portugal is unlike other uses of ceramic tiles in places like the Netherlands, Italy and Spain. In Portugal, azulejos are inextricably connected with the architecture, whereas in places like Morocco and the Netherlands you can remove the tile panels and transfer them to another place. In Portugal’s use of azulejos, if you remove a panel of the tiles you’ve lost something, because they’re connected to the architecture and are the decoration of the architecture itself.

HEREIN: How has the use of azulejos evolved in Portugal throughout the centuries?

PAIS: Azulejos have been used during very important moments in Portugal from the 15th century through today, and they’re always being reinvented in each moment to relate to different aspects of events that are taking place in our country.

The first use of azulejos in Portugal can be traced back to the late 15the century. By the 16th century, Portugal was importing azulejos from Spain, and this is the moment the Portuguese were experimenting with using azulejos from other countries. We call it the experimental period.

The 17th century in Portugal was by far the century of patterns. We’ve identified more than 1,000 patterns and are still discovering new patterns from that era. In the 18th century, narratives entered azulejos. This is the period of the blue and white tiles you can see so many examples of, but that was really a short window in Portugal’s azulejos history. During this century, churches and palaces became like books you could read, with stories and narratives told through their azulejos. The interior walls of the architecture became experimental during this era, you are looking at them and reading the narrative and stories.

The 19th century saw azulejos being put on the facades of buildings for the first time, embellishing their exteriors. The bourgeoisie began using azulejos on their own residences during this time to identify their houses and show they had importance and money. So azulejos became a statement of a new class in society.

Then came the 20th century, the moment we see azulejos used as urban art in the city squares, train stations and parks. The subway in Lisbon is considered one of the most beautiful in the world because it’s filled with azulejos. Each station has its own identity and the most important artists of the 20th century were commissioned to create them.

HEREIN: How is the 21st century shaping up for the expression of azulejos in Portugal?

PAIS: Today, we are facing new challenges as a society in Portugal and the use of azulejos is adapting with that. They are being used in the expressions of graffiti artists in Portugal to convey cultural issues. And now that those expressions are being made with azulejos (instead of spray paint), they’re no longer ephemeral. They can potentially last forever. Graffiti with azulejos is almost a perversion of the concept of graffiti.

We have graphic artists making azulejos and people using pixelated images that are transferred to azulejos. They’re using 3D elements transferred to them, too. So the composition itself now can be in three dimensions.

Because this century is so young, we don’t exactly know what all the expressions of azulejos will be. Only by the end of the 21st century will we see the whole story of this century’s evolution of Portuguese azulejos.

HEREIN: Have there been any exciting new recent discoveries or learnings in Portugal when it comes to azulejos?

PAIS: We had two very recent discoveries in the last three years that changed the history of azulejos. Near Lisbon, a 17th century find in a private palace changed our perception of patterns in azulejos. We always said there was no 8 by 8 pattern until this was found.

And just last year, in Torres Novas in a place that was to be destroyed, we found a series of azulejos that changed our perception of them, too. Until last year, we understood all the patterns in azulejos to be geometric or with vegetal patterns, like flowers, repeated. But last year we found human figures repeated in patterns on azulejos for the very first time. They are the faces of angels from azulejos that date to the beginning of the 17th century. They’re currently being restored so they can be put on display for the public in the museum.

HEREIN: Beyond Lisbon and Porto, where else will visitors be wowed by beautiful examples of azulejos around Portugal?

PAIS: Évora is a very important city in the south of Portugal with a lot of monuments made with azulejos. Also, Braga and Coimbra. Coimbra had a production in the 18th century that was really different from that of Lisbon and the rest of Portugal at the time. You can go all over the country–including the Portuguese islands in the Azores and Madeira–and find places with azulejos.