The East Village culture scene, as it developed through the late 1970s into the ‘80s, sought to decapitalize art. The art was taken out of the sterile, inhumane gallery/museum space and integrated into the crowded, teeming East Village: small storefronts, former tenements, and basement dance floors. The art was not precious, rarely archival, and often unsellable, whether because the work was installation based or so concurrent with living that it couldn’t be isolated and packaged for sale.

That’s a stance that seems unimaginable in our current moment, in which the supposition that value delivers meaning is granted in our culture, in our politics, and in our art. For us to pay any attention at all, the precondition is monetary value. The contextualization of art as capital dominates how we buy art, how we look at art, how we “own” art, how we discuss art, and how we historicize art. The auctions, the white walls, the celeb-fetishistic projection of the artist: The present-day art world reserves art for those who understand that art can be art only if it is worth something. Once, Keith Haring’s Pop Shop, which sold small pieces and fabricated baubles, exemplified the the East Village challenge to the art market. Today, that challenge is little more than a perceived liability to the normative market, leading to a welter of authentication problems and online offerings of forgeries.

David Wojnarowicz was indicial of the East Village temperament: a damaged, radical contrarian whose work nevertheless manifested an achingly open and optimistic sensibility, as is evidenced by the current retrospective at the Whitney, David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night. The Whitney’s long-expected look at Wojnarowicz is the first major museum exhibition for the artist in New York since the New Museum’s in 1999. Wojnarowicz, who died in 1992 of AIDS, worked in mixed media, painting, photography, film, music, and performance. He was a shy yet central player in the East Village and exemplified a community that shared ideas, images, culture, and even money.

The attitude first took discernable form in Wojnarowicz’s work in the 1978–79 series, Rimbaud in New York; a selection of the photographs and an Arthur Rimbaud mask are at the Whitney. In the photographs, the 24-year-old Wojnarowicz posed his friends, wearing a photocopied Rimbaud mask, around the city: Times Square, late-night diners, Coney Island, and other locations evoking the artist as romantic. Wojnarowicz venerates and deconstructs the artist as hero, bringing the conceit, deeply felt but deeply distant, to the immediacy of his city. The Rimbaud of Wojnarowicz’s mask is a cutout, a crime-scene body outline; the life in the images comes from the people Wojnarowicz photographs.

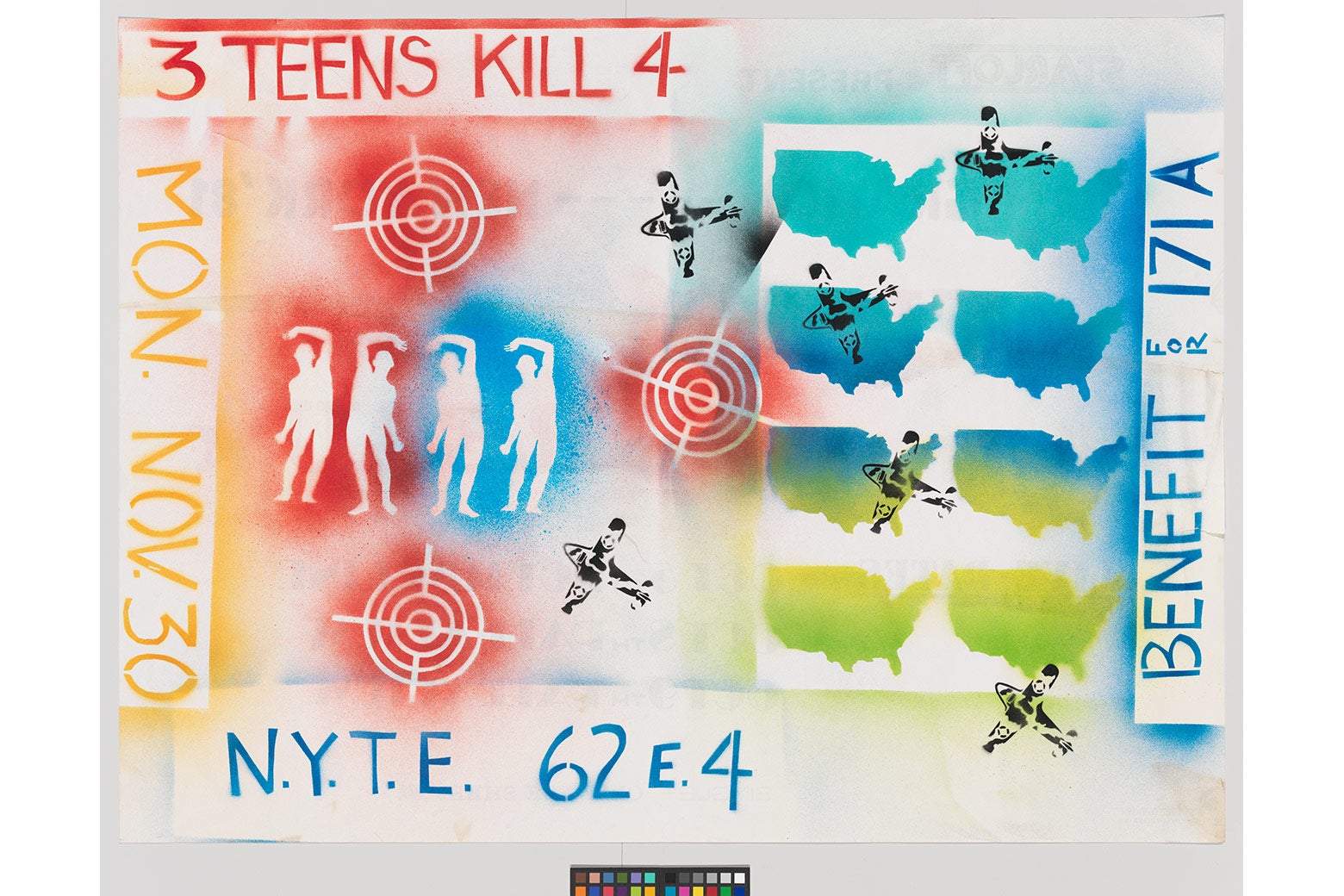

Within New York, the East Village—the location and the moment—was a superhub of intersections. Tribeca and SoHo had offered big lofts and empty streets to previous decades of New York City artists: zoning and the types of spaces, warehouse and light industry, hadn’t supported a local community. Priced out of those neighborhoods, younger artists were discovering the East Village, as well as the Bronx, where they encountered urban populations with their own contemporary take on the arts. Graffiti was part of the aesthetic (the posterized sensibility of the Rimbaud mask summons street art) and a new nightlife adopted attitude and characteristics from a midlife punk scene, disco, and the political happenings, often performance, of the later ’60s and ’70s. The misfits of the city had found each other, and a creative arena that allowed them not just to make a particular kind of painting or sculpture, but form bands (Wojnarowicz was a part of the proto-punk band 3 Teens Kill 4; songs are available on the Whitney website, and the band remains together to this day), stage fashion shows, and put on spectacles where and while people drank and danced. Art was part of the celebration.

The milieu was one of collective creation and an insistence that having fun, and largely outside the parameters of presumed social constructs, was art at its most legitimate. This is an argument that, sadly, the East Village did not win—and even in the Whitney’s thoughtful, extensive exhibition of Wojnarowicz, the impression is one of singular achievement. In retrospect, the familiarity of Wojnarowicz’s iconography is shocking: the falling man, the ink-boy figure, the dog-headed walker—we know these forms from Keith Haring, as well as from other artists of the period. The development of the images was shared; the reflex to attribute creation to a lone author is a contemporary anachronism.

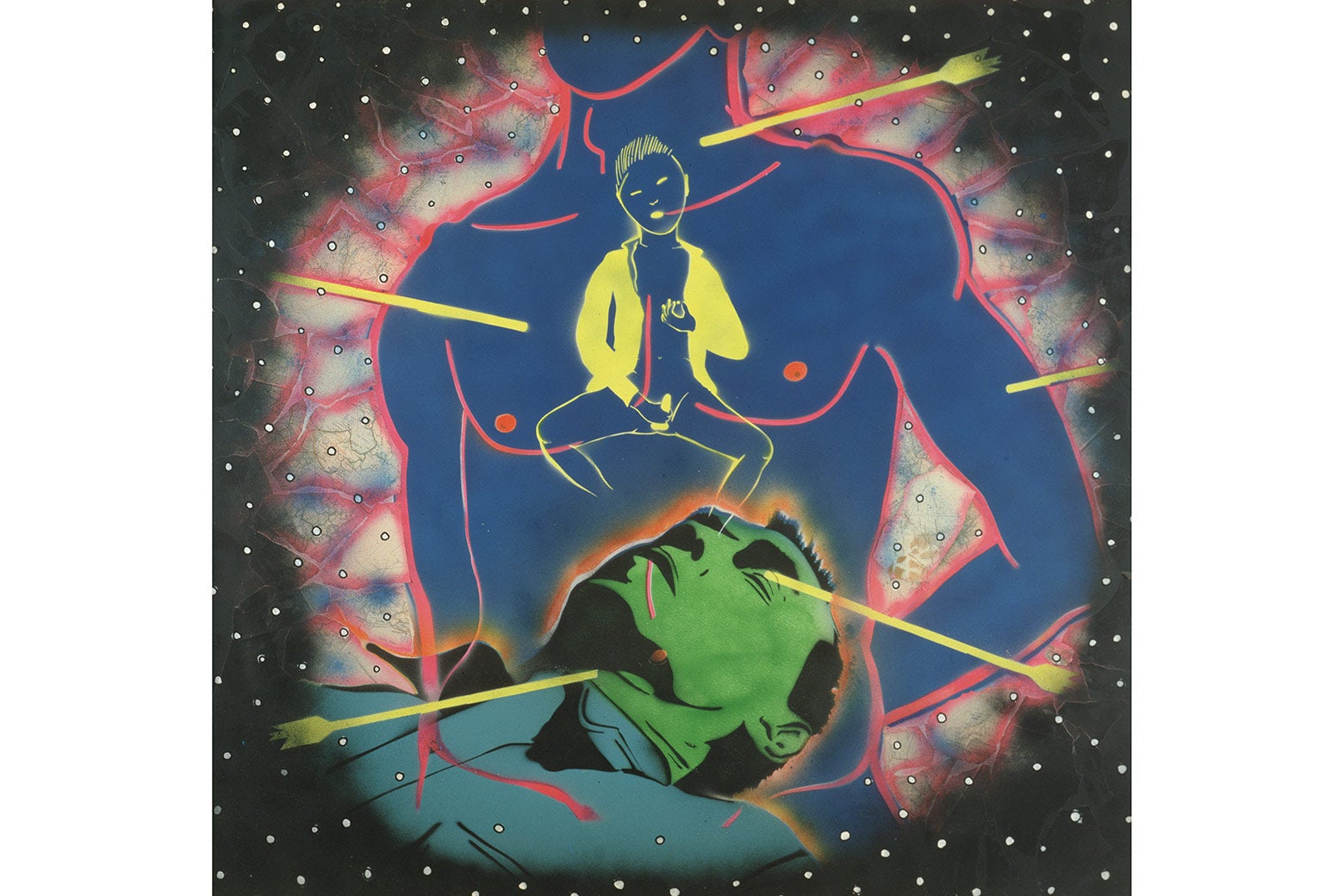

Connecting Wojnarowicz’s work pre-AIDS/HIV diagnosis with his work post-AIDS/HIV diagnosis is not intellectually difficult. The urgency and fury of the later work is brought on by an epidemic that was homicidally neglected by state, federal, and local government in the United States. Emotionally, it’s much harder to bridge before and after. Not only has the tone of the work changed, but a viewer’s perception is profoundly recast. Wojnarowicz’s Peter Hujar Dreaming/Yukio Mishima: Saint Sebastian, a sensitive portrait of a gay man dreaming, seems, after AIDS/HIV, like a portent, a man entering his own night terror.

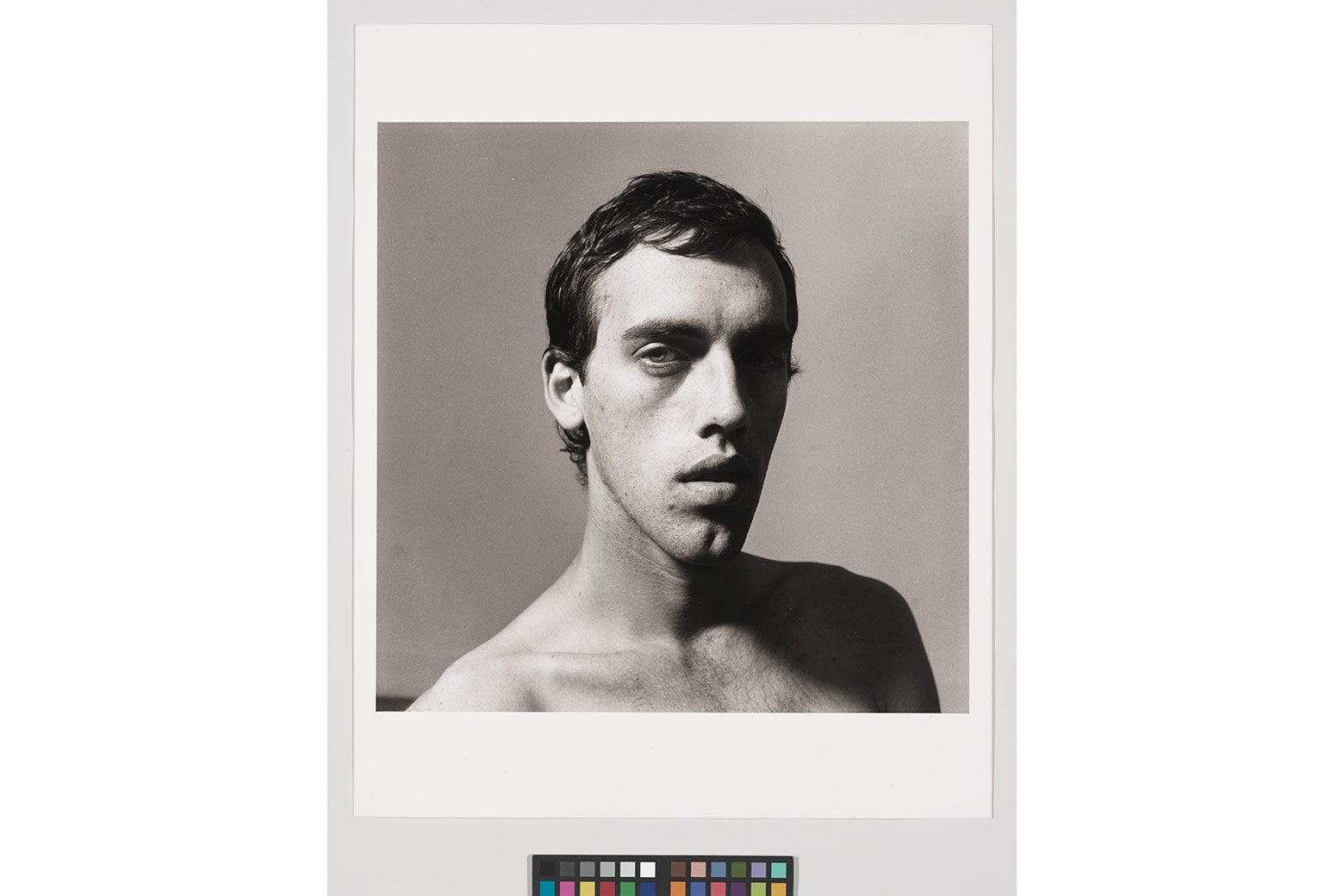

History Keeps Me Awake at Night places examples of pre-HIV and post-HIV work together, seeking to overcome the chasm. For example, the exhibition pairs photographs of Wojnarowicz taken by Peter Hujar early in the 1980s with photos of Hujar taken by Wojnarowicz, just moments after Hujar’s death due to AIDS-related pneumonia in 1987. The Hujar portraits of Wojnarowicz capture Wojnarowicz’s odd majesty; Hujar was a maestro of portraiture and photographic technique. The sensitive Wojnarowicz portraits of Hujar, his lover and mentor, testify to the friendship, the artistic exchange, and the shared horror of AIDS and the death-dealing intolerance of the nation.

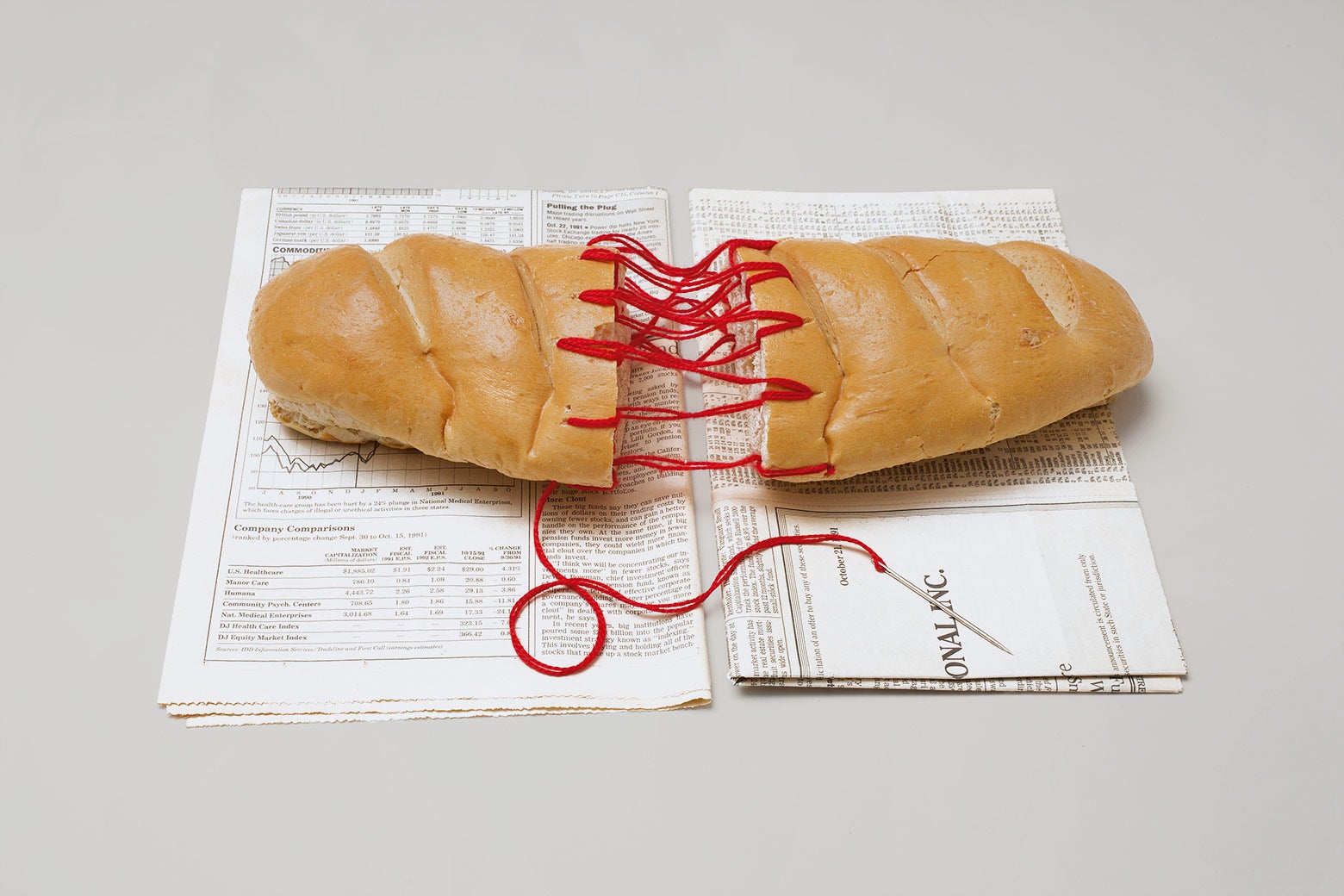

There’s a great deal of work exhibited at History Keeps Me Awake at Night, more than one expects—but perhaps most surprising is the immediacy and originality of Wojnarowicz’s color, and the meticulous technique in everything he did. Wojnarowicz’s multimedia approach was not haphazard; in later works, he carefully stitched panels into panels, much in the same way that he stitched together his own lips in the 1989 work, Silence=Death, or two halves of a loaf of bread in his film, A Fire in My Belly (1986). Though the film would remain unfinished, he would repeatedly elaborate on its images and themes: cartography, disembodied heads, injuries, and a kind of melding of the human and animal spirit. Through his personal and political writings, and his responses to his controversial and national status, Wojnarowicz honed his use of text, which he incorporated into his compositions. Later works at the Whitney, viewed in tandem with works on view at a concurrent Wojnarowicz show at New York’s PPOW gallery, also attest to a totemic kinship with Georgia O’Keeffe—skulls and flowers—who passed away in 1986.

If Wojnarowicz had lived, he’d be almost 64, and we’d still be going to shows of new work—talking about his latest. Wojnarowicz himself resisted categorization as a purely political artist, telling Terry Gross in 1990, two years before his death at 37, that AIDS was a part of his work but not his only concern: “I’ve always painted what I see, and what I experience, and what I perceive, so it naturally has a place in the work. I think not all the work I do is about AIDS or deals with AIDS, but I think the threads of it are in the other work as well.” The reduction of art for political purposes was something Wojnarowicz objected to enough to sue the American Family Association for reproducing decontextualized details of his work that were misrepresented as the works in their entirety. (He won and was awarded a check for $1, which is on display in the Whitney’s exhibition.) In the essay Wojnarowicz contributed to the catalog for Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing, a show curated in 1989 by Nan Goldin at Artists Space that gave artists a platform to respond to the AIDS crisis, he wrote: “When I was told that I’d contracted this virus it didn’t take me long to realize that I’d contracted a diseased society, as well.”

That the Whitney now occupies the once Meatpacking District is a bizarre irony of the show. The seedy site was one of the locations of Wojnarowicz’s Rimbaud photos, and into the late ’80s was the city’s red-light district for trans prostitution. Now, New York City’s misfits are supplanted by international tourists, vendors selling trinkets, and Diane von Furstenberg’s flagship store. And the 2018 art world is even better defended against the democratization of art than it was in 1980. Wojnarowicz had a spanning vision, in medium, subject matter, and humanity. He emerged from a New York City oeuvre that had an insight into the value of art, which of course was not a price but a better experience of living, a better way to be dynamic and forceful and courageous, and a better way to ask for a future. As he wrote in his 1991 memoir, Close to the Knives: “All I want is some kind of grace.”