When I think about the many women who have thrown very vocal support behind Johnny Depp as his defamation trial against his ex-wife, Amber Heard, winds to a close, I’m reminded of a joke shared among my closest female friends. Too often, in the course of our adult lives, we have, or have spoken with other women who have, rationalized not leaving a problematic male partner. The defense is always roughly the same: “You don’t know him like I do.” What’s funny about this? Mostly nothing, but mocking the reality that so many of us have struggled to leave these relationships offers a touch of levity in the face of the crushing weight of bad men in our lives. (Update, June 1, 3:32 p.m.: The jury found that Heard defamed Depp, awarding him $15 million. Heard was awarded $2 million in compensatory damages.)

Heard managed to extract herself from her marriage to Depp, but many of his fans have been far slower to turn their backs. The hashtag #justiceforjohnnydepp has billions of views on TikTok, while #IStandWithJohnnyDepp regularly trends on Twitter. How do we make sense of their loyalty, despite all that’s been revealed of his behavior? Yes, we can chalk some of this support up to ingrained cultural lessons: We have been told again and again to disbelieve women and revere men. But this explanation doesn’t adequately square many of the details being reported from the courthouse. It seems Depp’s celebrity—the way he has embodied characters at the margins over the course of his career—has created an inescapable sense of intimacy among his female fans.

To put it another way, while the trial is in some ways a referendum on #MeToo, some Depp fans seem to be dressing up and filing into the courthouse day after day for a simple reason: “You don’t know Johnny like I do.”

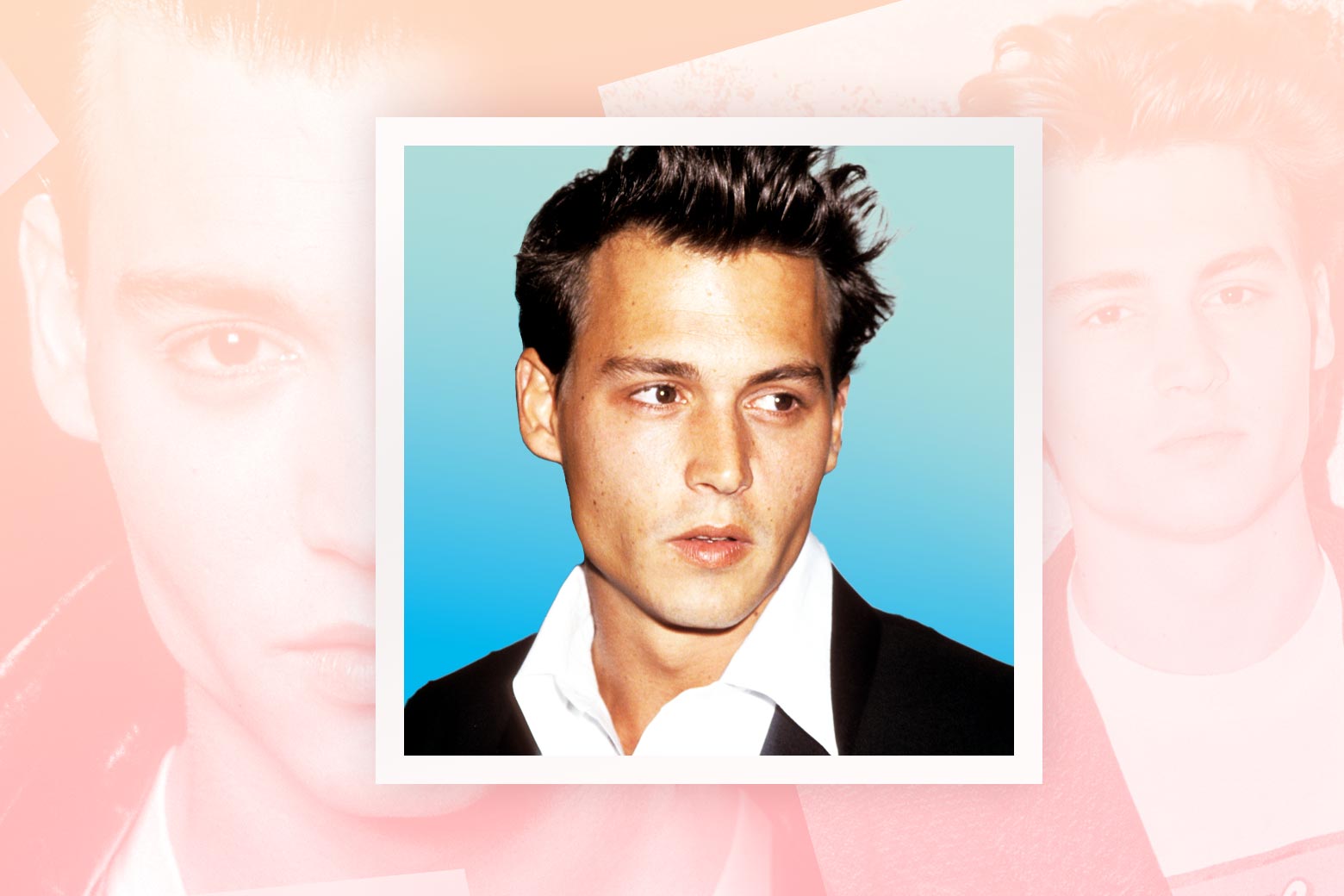

The women who show up to the courthouse, the Washington Post reported at the start of the trial, “feel like they truly know the actor.” His fans “call him a “sweetheart” or “down to earth” or say that he just “always seemed like a really nice guy.” I get what they mean. I was a teenage Depp fan. I hesitate to even type this, but my AIM handle was Deppstyle. At the peak of his career, Depp was an alternative to the stereotypical leading man. He gave life to a set of misunderstood outsiders: Edward Scissorhands, Gilbert Grape, Ed Wood, Cry-Baby. Off screen, he was soft-spoken, laid-back, and girlishly beautiful (those cheekbones!). Depp operated in contrast to the overtly macho, confident jocks who mostly dominated teenage coming-of-age stories in the ’90s.

That a man could be misunderstood, soft, or awkward was a welcome and hopeful thing. This alternate construction of masculinity struck at the heart of the more conventional formulations that depict a certain grade of masculinity as an immutable, essential fact: Men are tough, self-assured, they do not hesitate or doubt—they take action. Often, there was little room to understand their interior world. You will not be let in, try as you might.

Depp seemed different. Looking back, my fascination can easily be summed up by the movie Cry-Baby, in which Depp plays a motorcycle-riding rebel with a “heart of gold” who wins the affection of the good girl. As an adult, I am equal parts amused and embarrassed by the power that such a bad-boy-good-girl love story had over me. But I was sold on Depp by the time the movie came to a dramatic end with a game of chicken, and a victorious Cry-Baby, who sports a single teardrop tattoo representing his yearning for his goody-two-shoes lover, has finally learned to cry from both eyes.

Depp is not his characters. He never was. But like many teenagers, I was partially constructing my understanding of reality, men, and relationships through those movies. At the same time, Depp’s interviews about his career choices only deepened my interest and identification with him. “While he could have had a conventional career as a leading man, he has instead made a career choosing unusual roles,” Charlie Rose remarked during an interview with the actor in 1999. (Rose has since been accused of serial sexual harassment.) Over the course of their 20 minutes together, Depp explained his reasons for making such unconventional choices. He expressed an uneasiness with being marketed as a teenage heartthrob during the nearly four years he played police officer Tom Hanson on 21 Jump Street, as he smoked a cigarette and tucked a few tendrils of a chin-length bob behind his ear. “I was without question a product,” he said. “Not my own product. Somebody else’s product.”

What strikes me most about Depp’s attitude now is that he is articulating a relationship to Hollywood that is more common among women. His misgivings about not having control over his image are intensified by the loss of privacy that accompanies fame. “Even more than just the loss of privacy, just the aggressive invasion of your private life,” he said. “It is very strange, because you are treated in some circumstances as a novelty. And that is a very uncomfortable position to be in.” Even the anecdote Rose uses to remind Depp of his dwindling anonymity—the swarm of photographers surrounding the hospital during the birth of his daughter—is more often the experience of famous women. “The interesting thing as you were telling me, I thought, has nothing changed since the tragedy of Diana?” Rose asked. “No, no, I don’t think, no,” Depp replied, brushing his hair out of his face.

I am sure I didn’t fully understand his sentiments at the time, but Depp is articulating what it feels like to be objectified. His “uncomfortable position” as an object of desire without full agency over his own life and image is something teenage girls understand viscerally.

This sense of understanding is powerful. Much of the adoration for Depp seems to turn on a perceived or desired sense of intimacy with the actor. When Depp lost his defamation case against the tabloid the Sun in 2020 after a U.K. court ruled it was fine for the paper to call him a “wife beater,” Guardian features writer Hadley Freeman wrote in similar terms of her faded affection for the embattled actor and his cohort of alternative male celebrities that dominated ’90s culture. “They signified not just a different kind of celebrity, but a different kind of masculinity: desirable but gentle, manly but girlish,” Freeman wrote. “If we dated them, we understood that our role would be to understand their souls.”

The current defamation case is, at least for Depp’s fans, a referendum on his soul. While a jury deliberates on whether Heard slandered the actor when she wrote about her experience of domestic violence in an op-ed for the Washington Post, many of Depp’s fans have already decided that he is not the kind of man who is capable of such violence. Forced to confront their own beliefs about a man they only know through the distorting distance of celebrity, they have chosen not to grapple with the details in front of them.

Their understanding of Depp is, in reality, just a projection. His characters are fictional. They don’t tell us anything about Depp’s inner emotional landscape, about his views on women, about his personal demons, about his capacity for violence against people he holds close. It may be hard to square Depp’s on-screen image with the idea that he might be a violent domestic abuser. If he is misunderstood, gentle, and different, the trial offers too devastating a foil.

This resistance to embracing a new and more complicated view of Depp protects against having to accept just how routine and regular domestic violence and violence against women actually is. The numbers may seem familiar, but they bear repeating: One in 3 women have experienced “some form of physical violence by an intimate partner.” Homicide, most often committed by an intimate partner, is the leading cause of death among pregnant women, a grim statistic that affects all women and Black women disproportionately.

It might feel impossible to connect these facts to the image of the man who spoke to you enough that you named your AIM handle for him, or who acted out a different kind of masculinity. You might instead be driven to analyze Amber Heard’s statements about her makeup or conspiracies about her lawyer, to prove she is the person responsible. In some sense, I get it. But many women don’t get to escape the truth. And for some like me—who gobbled up Depp’s early image, who put up posters in their bedroom and swooned over the misunderstood bad boy—it’s crucial to remember that intimacy is not the same thing as being safe from harm.