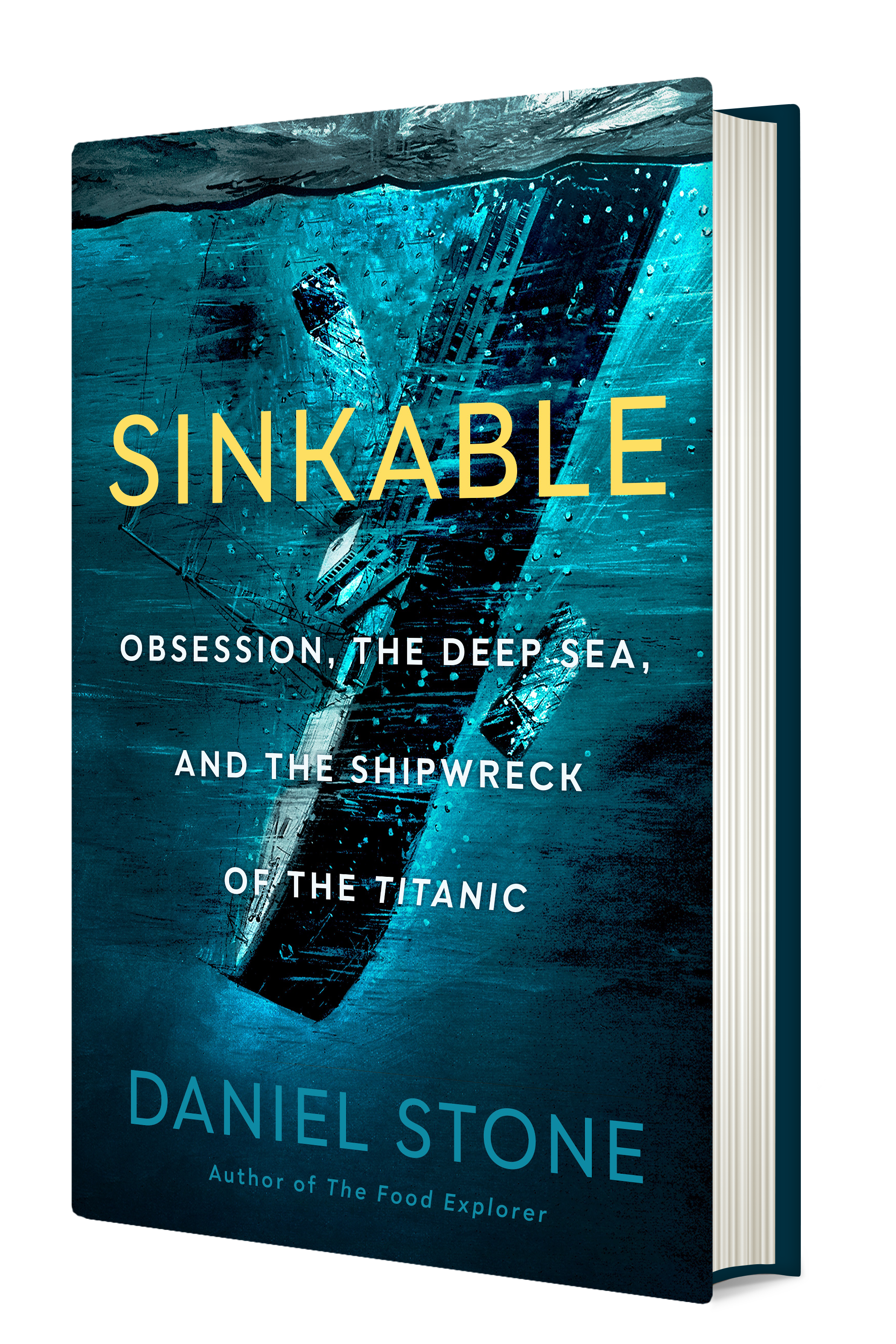

This essay has been adapted from SINKABLE: Obsession, the Deep Sea, and the Shipwreck of the Titanic.

Like almost every other ship on earth, the Titanic should have faded long ago into the background of history. That’s what happens to ships—we replace them, or, at best, keep them on life support as a museum, a hotel, or an IKEA lounge act. But the Titanic has lived on in our collective imagination for more than a century, inspiring countless books, films, TV specials, museum exhibits, musicals, and merchandise (you can even buy pieces of the rust destroying the Titanic on eBay). It’s still fascinating enough that some will even try to go down, at great risk and expense, to see what’s left of it. So what is it about the Titanic that made it the most celebrated shipwreck of all time?

Well first, it wasn’t the iceberg. Large ships had failed before and after the Titanic, many from collisions with icebergs. In 1854, the SS City of Glasgow disappeared on its way from Liverpool to Philadelphia, along with 480 people, after it was thought to hit an iceberg. The SS Naronic, en route from Liverpool to New York in 1893, also vanished, with 74 aboard. Not only was news of the Naronic met with apathy, it was also a complete mystery until messages were later found floating in bottles written by passengers who blamed their disappearance on an iceberg strike. Icebergs were such a common problem in the North Atlantic that, by 1912, most experts were relieved that collisions with icebergs appeared to have declined. Prior decades saw as many as seven strikes each month; by 1910, there were only about four per year.

It also wasn’t the death toll or the fact that the Titanic was considered unsinkable. Other wrecks had drawn greater losses of life, like the Chinese junk ship Tek Sing, whose 1,600 passengers were killed in 1822 when it ran aground in the South China Sea, or the French munitions ship Mont-Blanc, which sank in 1917 after an explosion so fierce in the harbor of Halifax that falling debris killed more than two thousand people on shore. “Unsinkable” was a very common term thrown around in the late 19th century in hopes it would convince insurance companies to reduce their premiums.

Then there are the retroactive reasons drummed up by historians to contextualize the ship and its place in history: that the Titanic was an embodiment of overconfidence or a lesson in humility for a world growing too fast. These theories aren’t wrong, they’re just too convenient, and they use selective facts to form a pat narrative.

So what was it? In a perverse way, the Titanic got lucky. Its century-long growth into a worldwide cultural phenomenon is rooted in two often overlooked factors: demographics and timing.

In most shipwrecks, either most people die or rescuers arrive and most people are saved. But the Titanic had a unique mix. About 1,500 people died, but 700 lived. Had every last soul drowned on the surface or been dragged to the seafloor, it would’ve been treated like most entries in the voluminous annals of devastating maritime tragedy. Memorials would have been held, insurance checks would have been paid, and the world would have moved on—especially as bigger events like world wars and depressions came along. But a tragedy with hundreds of survivors meant there would be hundreds of gripping accounts of the ship’s final moments, the wrestling and jockeying, the rescued and the abandoned, the bravery and the cowardice. There were many—and, at times, conflicting—tales for the public to adjudicate. History isn’t told by the dead.

Importantly, those 700 survivors were mostly women and children, whose youth ensured decades of telling and retelling their story. Eva Hart was seven in 1912 when she stepped into a lifeboat with her mother. She realized years later that the barely three-day experience during her childhood would become the centerpiece of her identity, and when no amount of changing the subject or politely declining to answer the same questions would be sufficient, she embraced the role. By the time she died in 1996, she had transformed into an Oprah-like figure who turned her early-life trauma into a message of resilience, perseverance, and hope.

And the particular timing of the disaster helped the survivors’ accounts travel further than they otherwise might have. The year 1912 was a very lucky time for a ship to sink with hundreds of survivors, because the 1910s coincided with the dawn of modern storytelling. It was getting easier to print and distribute books. Radios were the first live medium for news. The rise of film, and in the decades following, television, made it possible to tell, visualize, and share this great story far wider than the reach of a local broadsheet.* This helped vault the Titanic from a tragedy most Americans read about in newspapers to a vivid cultural moment shared by all. The first film made about the disaster, called Saved from the Titanic, was produced just 29 days after the ship sank (sadly the film’s only copies were destroyed in a fire in 1914). Two more films came later in 1912, one French and one German, which made the story accessible to millions. None of this would have happened if the ship sank 20 years earlier.

As the movies got better with the introduction of sound and color, writers could still consult survivors for first-person details. Nobody acquired more of this detail than Titanic historian Walter Lord, who in 1955 wrote a definitive account of the ship’s final hours called A Night to Remember. Lord’s book was extremely rich and filled with colorful anecdotes, which inspired a film by the same name in 1958. (On the day they filmed the sinking scene, an actual Titanic survivor named Lawrence Beesley showed up on set, asking if he could be an extra and “go down with the ship.” Scrambling in freezing water was apparently the only part of the Titanic story he didn’t get to experience. The director said no because Beesley lacked membership in the actor’s union).

I wasn’t alive in the 1960s, but my dad once told me that he watched A Night to Remember every day after school because it was on TV so much. I confirmed this with television records from the ’60s showing that the film inspired by Lord’s book was like The Shawshank Redemption of its day— endlessly findable and extremely gripping, but also true. I can’t imagine how many young kids—and boys seem to love the story especially—grew enraptured by the Titanic story. But I understand why. Lord’s film did something few historical events can: it made something that happened 50 years earlier feel fresh and modern.

And then another technological change came along that worked in favor of the ship’s legacy. The tale of the Titanic might have faded in the ’70s and ’80s if not for advances in underwater exploration that made it possible to find the corpse of the Titanic, which would solve long-running mysteries like whether it broke apart on the surface (eyewitnesses shared conflicting accounts). The search brought together colorful characters, many of whom had no expertise in deep-sea exploration. (I write about this band of misfits in my book Sinkable). When the wreck was found in 1985 by a Navy oceanographer, the world was enchanted anew by the first blurry images of a wreck they had heard about all their lives. What followed was a scramble for forensic clues and the pilfering of artifacts, both of which set off court battles and got heavy media coverage.

Seeing the world’s ravenous appetite for the Titanic story got a young Hollywood producer thinking. James Cameron apparently loved shipwrecks as a boy, and especially the Titanic, so he decided to do exactly what Walter Lord did—but instead of making a low-budget black-and-white film like A Night to Remember, Cameron wanted to create a cinematic experience filled with special effects and invented characters. This was a gamble, but a good one; Cameron could tell that the power of the Titanic story lies in the way it can be endlessly reinvented. And sure enough, his film, Titanic, went on to break worldwide box office records and win Best Picture.

In recent years, I was starting to think the Titanic story was running on fumes. What more was there to rehash? But it still shows up every few months in the news. New scans show the wreck in full detail. A new theory that the Titanic never actually sank goes viral on TikTok. A musical that tells the Titanic story from Celine Dion’s perspective is a Broadway hit. New tourism opportunities can take you to the site of the iceberg strike. A visiting exhibition of artifacts is coming to your town. After reading this, trust me, you’ll start to see it everywhere.

The loss of the Titan submersible will be another event that supercharges the story of the long-ago ocean liner. In many ways it adds to the tragedy—a ship carrying rich people was warned of danger and disappeared while visiting another ship that had also been carrying rich people, and was also warned of danger and disappeared. But it will also reinvent a long-ago story for a new generation, yet again. Gen Z now has its own point of entry into the Titanic story, and a sense that they experienced a part of its afterlife. Fame has a way of compounding. Like barnacles on a hull, people just can’t help but grab on.

Correction, June 26, 2023: This piece originally suggested that television began its rise in the 1910s. Its emergence began in the late 1920s.