The Beginning: Wújí (無極)

Classical Chinese philosophy starts at the very beginning; the time when all was still, there was no differentiation between things. There was only the one void, the vast emptiness. It is the infinite “no-thing” before there was “something”. It exists before all opposites (yin-yang) began to form. It is boundless. It is the state of being from which all other things are born. It is the primordial ground from which everything in the universe arises and plays itself out. In Chinese schools of philosophy, this is called Wújí (無極; wu-chi).

Together, the Chinese words wuji mean “unbound”, “limitless”, or “infinite”. Wu means “without, not to have, none, to lack.” Ji is a “roof ridge, ridgepole”.

Above all, wuji is deep and mysterious. Of this primordial state, the great fifth-century B.C.E. Daoist philosopher and writer Liezi (列子, Lieh-tzu) stated: “The ending and starting of things have no limit from which they began. The start of one is the end of another, the end of one is the start of another. Who knows which came first? But what is outside things, what was before events, I do not know.”

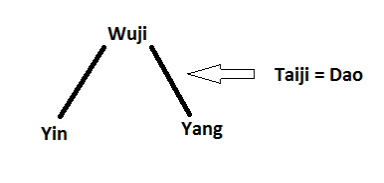

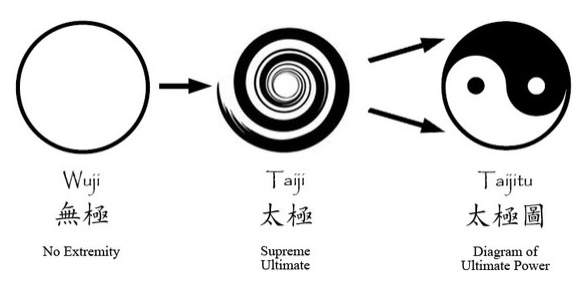

Once things in the universe began to vibrate and move, they began to separate and differentiate. In Chinese philosophy, this is the principle of Taiji, which is made up of yin and yang. This beginning movement of differentiation is often depicted pictorially as a spiral.

Of this process, the legendary founder of Daoism, and reputed author of DàodéJīng (道德经; Tao Te Ching), Laozi (老子, Lao-tzu) writes in the opening lines of chapter 42:

Dao gives birth to One

One gives birth to Two

Two gives birth to Three

Three give birth to ten-thousand things [meaning All Things]

The ten-thousand things carry yin and embrace yang

They mix these energies to enact harmony.

The Taiji Symbol (太极, Tàijí or Tai Chi)

Yin & Yang Philosophy (Yīn/Yáng; 陰陽)

What Are Yin and Yang?

Yīn Yáng (陰陽) is the concept in Daoist Tàijí philosophy used to describe seemingly opposite, yet complementary aspects of natural phenomena. Simple examples of the Yīn/Yáng concept include light/dark, stillness/motion, cold/hot, low/high and so forth.

Yīn/Yáng describes dualistic forces, which are interdependent and cannot exist independently of one another, together forming a mutual whole. If there is no light, one cannot talk about darkness. Without stillness, the concept of motion cannot exist. Furthermore, Yīn/Yáng are never absolute, as can be seen in the tàijítú (太極圖) symbol (also known as the Yīn/Yáng symbol). In the dark, there is the seed of light, and within the white, one finds the essence of black. They are dynamic and not static, constantly transforming each other and/or transforming into each other, seeking a relationship of dynamic balance.

Simply put, Yīn/Yáng is just a way of looking at the world. It’s the simple observation that the world is always changing, without the usual judgments of “good” or “bad” that we usually attach to things we observe. It is the observation that everything is relative and provisional, and that dynamic, ever-changing balance is the natural state of existence. It reminds us that happiness and fulfillment can be all in our frame of reference.

Yin and Yang refer to Complementary Opposites, as opposed to forces that are in conflict. Based on qualitative aspects, everything can be classified into Yīn or Yáng. These are opposite yet complementary aspects that together form a unified and complete whole. Originally, Yīn referred to the shady side of a mountain and Yáng the sunny side. The image is of one mountain, but two perspectives of it can be seen.

Speaking in broad general terms, Yīn is associated with less energetic qualities and Yáng with more energetic qualities, such as:

- Yīn: female, dark, night, cold, stillness, passive, lower, negative

- Yáng: male, light, day, hot, motion, active, upper, positive

Sometimes people are tempted to look at any of these qualities or expressions of yin or yang through the conceptual framework of the “good” or “bad” judgments. It is important to remember these are judgments based upon the human perspective and discriminations, not from the perspective of natural balance. Any of the aspects of yin or yang could be desirable or undesirable based upon the totality of the particular circumstances under which they are manifested, and upon how we relate or interact with them, not in some inherent quality they possess. Additionally, the qualities of both are needed to bring about balance; each one is on the extreme side and cannot bring about a state of balance on its own.

Yin and Yang are polar opposites, but one cannot be defined without the other. Male would not exist without female. If there is to be light, there must be dark. Heat would not exist without the cold. Without there being pain, we could not experience pleasure. If death did not exist there would be no new life. The list could go on for all time.

It is also important to remember that the quality of yin or yang is not a fixed, intrinsic quality in the thing itself, it’s all relative. It depends on the nature of the relationship between the things being compared. For example, 100° is yang when compared to 32°, which would be yin in this case. However, 32° would be yang when compared with 0°. One individual might be yang relative to height when compared to someone who is shorter, but yin when standing next to someone who is taller than they are. Day is considered yang, where nighttime is yin. However, dusk would be considered yin when compared with noon, but yang in relation to midnight. Therefore, the qualities of what is yin or yang are all a matter of relationships.

Interdependent & Relative

It is important to understand Yīn and Yáng are interdependent and relative. They cannot exist independently and together form a mutual whole. Without light, one cannot think about darkness. Without stillness, the concept of motion cannot exist. Heads and tails are two sides of the same coin.

Not Absolute

Nothing is ever completely Yīn or completely Yáng. This is reflected in the Yīn/Yáng symbol (called taiji tu), where the smaller dot within the larger half symbolizes that one side contains the seed of the other. The darkest night still has the potential for light, and the most masculine man may still have some feminine qualities.

The white area is embracing black and the black embraces the white. In martial arts practice, this teaches us that “in softness there is firmness and in yielding there is strength”. For our daily lives this means we must accept the bad experiences to have the good, and if we embrace those things in ourselves and our lives that we dislike, especially the things we feel we cannot change, they cannot prevent us from being happy. Yet, if we truly embrace these aspects, we come to understand them, and we may find they are not as difficult to transform as we may have thought. This, the principle to Taiji teaches us, is how we become truly strong, inside and out.

Dynamic, Not Static

Yīn and Yáng can transform each other and/or transform into each other. Day becomes night, and night becomes day again. In the Yīn/Yáng symbol, the black and white halves “chase” each other, which visually emphasizes the constant, cyclical nature of change.

Balanced Whole

According to this Daoist principle, balance between Yīn and Yáng is the natural state. Having the sun shine 24 hours a day would be just as unpleasant as having never-ending nights. However, the two elements do not have to be equal nor unchanging (think about a summer day vs. winter day). This is the relationship of dynamic balance between all things.

Taijitu

How does Yīn/Yáng relate to Taiji?

Tàijí (太极) is the mother of Yīn and Yáng. It is a foundation of the Daoist philosophy and view of the universe. The word Tàijí itself refers to the “great primal beginning” of all that exists and is often translated as the ‘Supreme Ultimate’. Comparable to the initial state of the universe at the exact moment of its creation, Taiji is the state of absolute and infinite potential. From this state, the poles of Yīn and Yáng were generated. In other words, Taiji is the absolute (the circle), while Yīn/Yáng is the relative (the two halves). Thus the Yīn/Yáng symbol is more correctly referred to as the Tàijí symbol (Tàijítú, 太极图).

Two different ways to illustrate the movement within Wuji to form yin and Yang:

How do Yīn/Yáng and Taijitu relate to the practice of Taijiquan or other Chinese martial arts?

Tàijíquán (太極拳) is the application of the Yīn/Yáng concept in a martial arts context. Though we should recognize that this is one interpretation and, in fact, all Chinese martial arts (and more widely, all of the Chinese culture itself) utilize this foundational Chinese philosophical principle. Particular attention is placed on the existence and balance of dualistic forces with respect to physical motion and mental intention. By following the natural laws of Yīn/Yáng in the body, one develops a more fluid, efficient and powerful movement.

Some generalizations can help explain this concept:

Hard / Soft

Rarely in the practice of Taijiquan do you meet force with force. Instead, Tàijíquán emphasizes ‘soft’ yielding techniques to neutralize or move around ‘hard’ force. However, if the opponent provides a soft opening, then one would strike to penetrate with ‘hard’ force.

Solid / Empty

Most often this describes whether one leg carries more or less weight, and how weight shifts between them and moves the body through the environment we are in. The body and the arms, too, can become “full” and firm, or soft and whipping, depending upon the needs of the given circumstance.

Expanding / Contracting

This most directly describes how movements must alternate between outward and inward motions, or opening and closing movements. Other examples include inhaling/exhaling, advancing/retreating, rising/sinking and activity/resting.

Many people have a misunderstanding about the practice of internal martial arts or qigong. They are not about special movements, because the movements and techniques themselves carry no inherent power. The real principles here are about efficient body structure and mechanics, and the interplay of the relative energies of yin and yang within the body. These dynamic relationships and changes can be between left and right, hard and soft, high and low, expanding and contracting, emptying and filling, and so on. When looking at practicing with another person, you then incorporate the elements of the interplay of yin and yang in relationship to the other.

On the most basic level, many internal martial artists and qigong players aim for the highest levels, while overlooking the basic principles of body structure and yin-yang interplay. These are not unseen forces, but very tangible and experiential. In your own practice, see if you can notice these forces for yourself. With practice, this ability will become second nature. By becoming aware of and following the natural laws of yin/yang in the body, you can develop more fluid, efficient and powerful movements. This is what is meant when one states that Taijiquan is an “internal” art, as opposed to focusing strictly on external factors. Internal refers to being mindful and aware of how the body feels, meaning specifically balanced and stable, rather than being concerned foremost with how the hands and legs move.

This really help me with the history of taijitu 谢谢 大家

LikeLike

Thank you. Being of some help to those who practice these arts is my only goal.

LikeLike