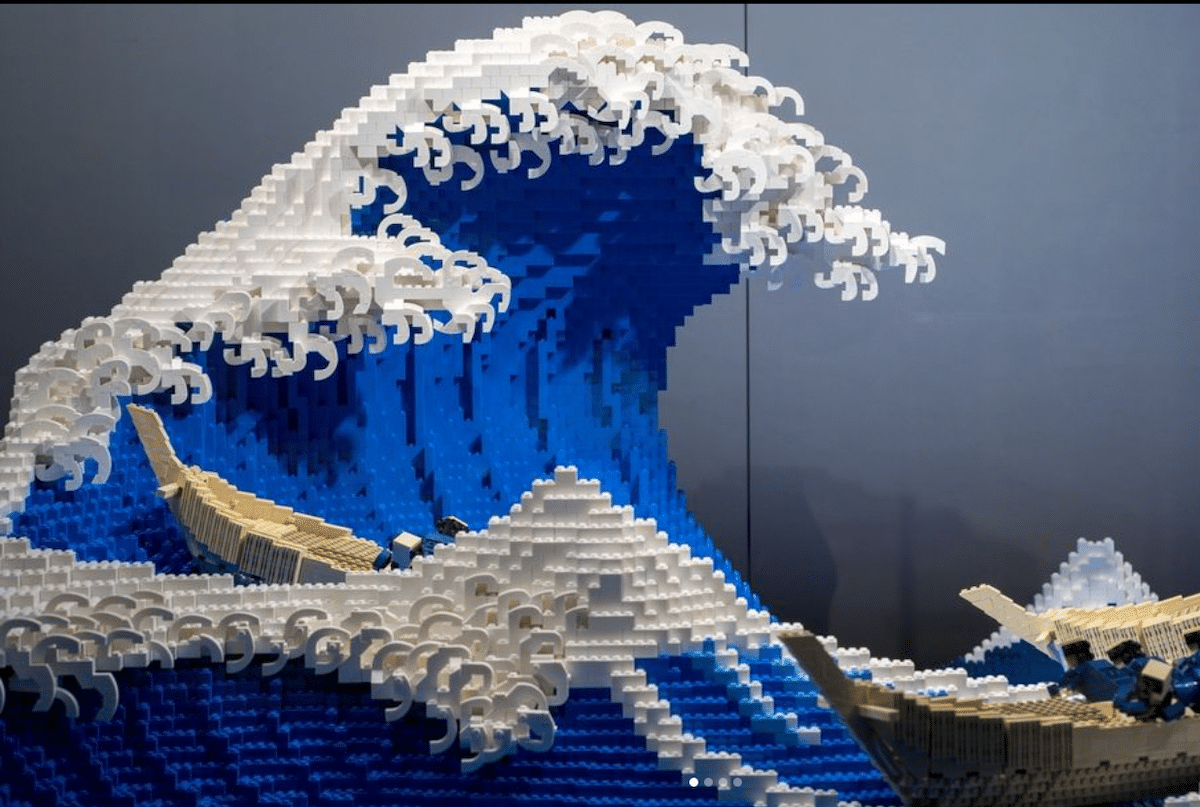

You know the image.

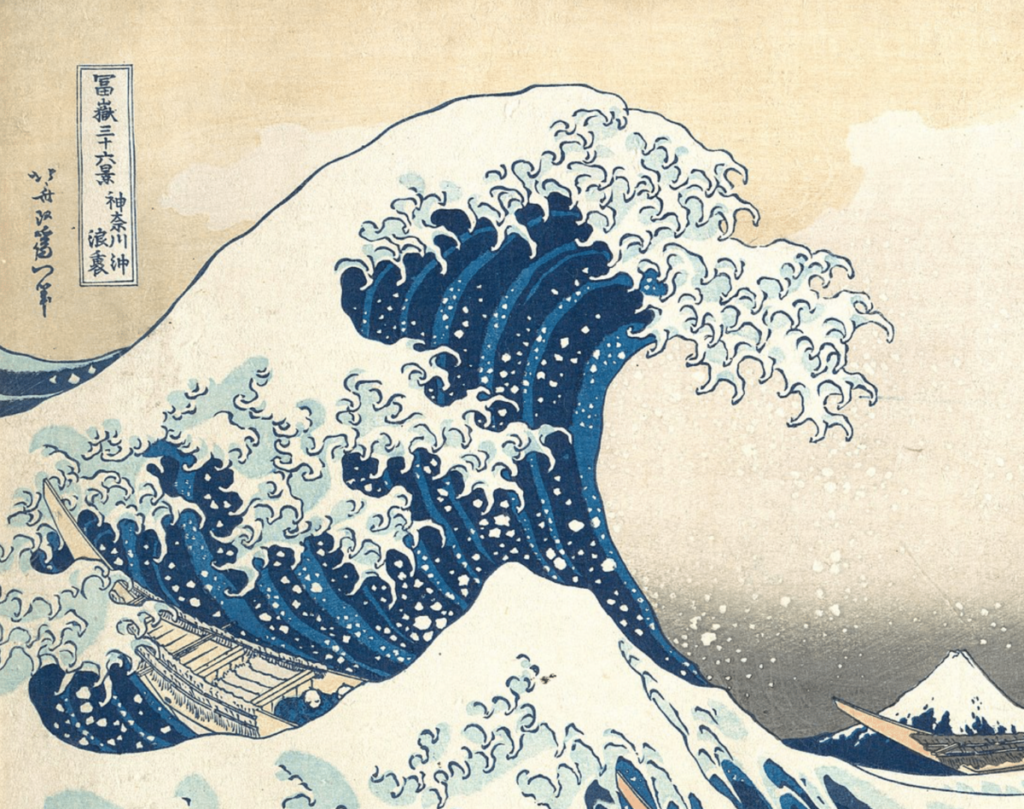

“From Claude Monet and Loïs Mailou Jones to Roy Lichtenstein and Yoshitomo Nara, countless artists have drawn inspiration from Katsushika Hokusai.” So says the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, which has built an exhibition around Hokusai’s iconic woodblock print, The Great Wave. The show traces the “ripple effects” Hokusai’s image has had across multiple artists and time periods in the global history of art.

Simultaneously, one of the last prints from the original edition of The Great Wave, created between 1830 and 1832, broke records at auction when it sold for nearly $2.8 million a couple of weeks ago. This print of The Great Wave was said to be in the finest condition of the few remaining examples not held by a museum. The final selling price was more than had ever been paid for one of Hokusai’s prints.

The image was created as part of a series titled Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, a study of Japan’s active volcano mountain, created during the last years of the Edo period (1603–1867) of Japanese history using a woodblock printing style called Ukiyo-e.

This generally inexpensive print, “was designed to be mass-produced and would have cost the same price as a typically cheap meal like a bowl of noodle soup,” according to art news site Hyperallergic. “While popular decorations, woodblock prints like Hokusai’s were not considered fine art during their time.

Still, “The Great Wave” stood out when Hokusai first printed the artwork for its use of Prussian blue, a new synthetic dye imported from China and the Netherlands that resisted fading, unlike indigo or dayflower blues. The whole Fuji series was a best-selling success at the time.”

But Why this Image?

Why was, and is, this particular print, among the tens of thousands of others made before and after it, so persistently popular? It’s been made into tee-shirts, posters, bathing suits, umbrellas, mugs, you name it; it’s even an emoji.

The auction house that sold the early edition print was at pains to explain why the image has become so iconic, pointing to its narrative content (man against nature – but how many people notice the three imperiled boats of rowers?) and the “dichotomy of beauty and terror,” which, actually, is as good an argument as any, I’d say.

Detail: Hokusai’s Great Wave

However, what none of the curators mention is something perhaps only an artist would fully understand – the character of the foam. It’s not at all realistic; the artist had to make it up, and he did so in a strongly expressive way. “Expressive of what,” you might ask, and I’d answer, of a very basic and universal response – a strong example of what, in art, is called the artist’s feeling.

Hokusai depicts a massive, surging natural force, overwhelming in its momentum, churning across the sky. He’s shown it to be made up of hundreds of smaller components (a wave is just a collection of droplets after all) – and (and here’s why I think this print is immortal) they seem like hands. Do they not?

To me, the Great Wave is visually clawing its way up out of and across the surface of the sea. The boats about to be swallowed up add proportion and a whole lot of drama. But all of this sharply taloned, grasping foam, dissolving into dozens of what resemble tiny curled hands or claws suggesting motion, is surreal and poetic. It’s poetic because it alchemizes a familiar natural phenomenon into a psychologically charged image.

Hokusai’s wave was unprecedented in art, but the real reason we know it so well is that it is inimitable still. By which I mean, the way he depicted the wave is so powerful that anyone who really looks at it is gripped and impressed upon by the image.

At the same time, it’s so original and specific to this artist and none other that anyone who paints a wave remotely like owes an obvious debt to Hokusai. And that’s what the show at the MFA – and all good art, really – is all about.

Making Waves with the Pros

Lisa Egeli, Good Things Come, 8 x 18 oil

Painting ocean waves is not as complicated as you might think; there’s a basic formula and known, teachable techniques for creating compelling seascapes.

You can learn how to paint a sweeping coastline with crashing and rolling waves, reflections of light on wet sand and craggy rock faces, and much, much more.

A wide range or just about all you need to know is revealed, step by step, in these two videos, available as a one-two-punch bundle for a limited time: Lisa Egeli / Emery Bowling Seascape Combo.