John Martin’s fame, already far-reaching, continued to grow long after he died in 1854. By the 1880s, more than 8 million people across the Western world, in shows from Dundee to Dublin and Sydney to New York, had fallen under his hypnotic spell: who could fail to be entranced by his spectacular paintings of biblical catastrophe, end-of-empire chaos and scenes of heaven and hell? Yet more still would have been shocked and thrilled by Martin’s exceptional visions, as reproductions in newspapers and prints copied by others, and even as originals sold by Martin himself.

The circumstances of those exhibitions reveal just how popular Martin’s paintings were. They were seen not only in galleries but in commercial and civic venues, theatres and music halls. As curator Martin Myrone explains: ‘The pictures were hyped up relentlessly, with half-price ticket offers (for Sunday school children!), evening displays by gaslight, heavy-handed advertising and special descriptive lectures.’ 1

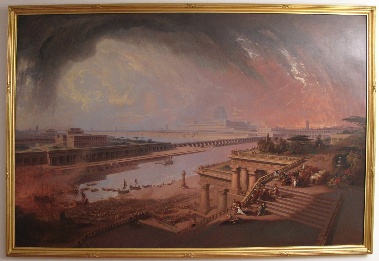

Tate Britain shouldn’t expect the same frenzied clamour (or 8 million visitors), but its new show John Martin: Apocalypse deserves to draw the crowds. This is the most extensive coverage of his work since Victorian times and after many years of critical neglect, Martin is long overdue fresh evaluation. The exhibition charts his ‘rise, fall and resurrection’, and showcases his most important paintings – including a restored lost masterpiece, The Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum (1822) – as well as mezzotint illustrations and a number of landscape watercolours. It also centres on Martin’s other life as an urban planner, including his scheme for the embankment of the Thames and a railway he designed to encircle London. His influence on the minds of others however, is perhaps his greatest achievement.

Advertisement

It wasn’t just the public – many of whom understood what they saw as insights into biblical truth – who were influenced by Martin. His impact on contemporary visual culture, especially blockbuster entertainment, is huge. We know DW Griffith kept an image of Belshazzar’s Feast(1820) in his scrap-book, which inspired the Babylon sequence in his 1916 silent movie Intolerance, and we know Hollywood special effects master Ray Harryhausen was likewise inspired: the backdrop of Olympus in 1981 movie Clash of the Titans was the city from Martin’s Joshua Commanding the Sun to Stand Still upon Gideon (1816).

According the show’s free booklet, another terrifying image, mezzotint Satan in Council (1831), is the clear inspiration for the Jedi council meeting in George Lucas’ The Phantom Menace(1999). You can even see his influence in the art of Derek Riggs, who painted the iconic 1980s Iron Maiden album covers using the demonic, monumental, end-of-the-world grammar (and lightning-drawn-with-a-ruler technique) pioneered by this most popular of artists.

But perhaps his most significant admirer, and one sadly not mentioned in the exhibition, was an architect: Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson. This inventive British architect never left these shores – or rarely even the streets of Glasgow – yet through his stated affection for the ‘magnificent architectural compositions of the late John Martin’, his designs transformed his native city into a sensual Corinth of the north. 2

Martin’s paintings are furnished with buildings of the most powerful kind: vast cubic masses playing against each other, indeterminable colonnades of some unknowable order, temples of inconceivable solemnity and exotic style.3 To the deeply religious Thomson, it appeared to be the perfect territory, spiritually and creatively, for imaginative appropriation. 4As HS Goodhart-Rendel remarked in his celebrated lecture ‘Rogue Architects of the Victorian Era’: ‘In the middle distance of the Fall of Babylonor the Last Judgement [Thomson’s] United Presbyterian churches would not look at all amiss.’ 5

It is not known if Thomson saw Belshazzar’s Feast when it came to Glasgow in 1821. He would have been just a small boy. The show was part of a nationwide tour organised by Martin’s former employer, the glass painter William Collins, who was keen to make a return on his dazzling investment. Yet 50 years later, the incredible facade of the Egyptian Halls, an office and warehouse on Union Street (currently under threat of demolition), would illustrate Thomson’s obsession with Martin’s architectural imagery more thoroughly than any of his other buildings. Its stacked horizontal layers of picturesque colonnades, a fusion of Greek, Roman, Egyptian and Romanesque references, seem directly transplanted from a canvas or mezzotint.

Advertisement

Thomson’s fertile imagination nicely overturns the cliché that travel broadens the mind, and so does the work of Alan Moore, the eccentric comic-book writer who famously launched a magazine two years ago dedicated to his home town of Northampton. 6His many celebrated works resonate with a sense of foreboding and doom, and the curators of Apocalypse cite them as descendants of Martin’s imaginative scene setting. (It is an oversight to cite Moore and not Thomson, but perhaps that is because the Thomson-Martin connection deserves a show to itself.) Nevertheless, a line from Moore’s performance in Newcastle’s Laing Art Gallery last year, inspired by Martin’s The Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah (1852), is typical of the insight the author is famous for. It reads: ‘This is the terror of the world’s edge, is the vertigo of an accelerated culture. Out beyond the lights of every city, every town and every century, this is the abyss that abides.’ Martin’s paintings, Moore appears to suggest, operate on an almost musical level, in that they are tonal, emotional, sublime.

For some, Martin’s paintings served as a hubristic warning: it was the Victorians after all, who declared they had finally discovered all that there was to find. But the public’s appetite for knowledge and spectacle remained insatiable. In his book, The Shows of London(1978), literary historian Richard Altick describes a 19th-century exhibition culture fixated on freak shows, mechanical wonders, curiosities and fine art, and it is in this tradition that we must place Martin’s blockbuster paintings. His imagery exploited the taste for dioramas, panoramas and phantasmagoria shows of the day, the ‘vertigo’ of Moore’s ‘accelerated culture’. Martin’s debt to illuminated entertainment is clear.

That debt is honoured in a special effect all of Tate Britain’s making, when every half-hour the lights dim in room six (transformed into a ‘civic hall’ by Dow Jones Architects) and Martin’s most famous works, a triptych consisting of The Last Judgement, The Great Day of His Wrath and The Plains of Heaven(1849-53), is performed as a son et lumière. When the lights fade to black, a faint spot – like candlelight – drifts across the room and alights upon each of them, growing in size to frame larger and larger parts of the works. There is also a soundtrack of spoken words drawn from the Bible, from Martin’s own pamphlet describing the pictures,and from newspapers and magazines of the time. Then, remarkably, the paintings come alive, as high-resolution projections swirl, fade and even animated lightning strikes transform the delirious scenes. To some, this lightshow will be dismissed as pointless hokeyness, a step too far. Greek Thomson however, and 8 million others, would have absolutely loved it.

All works by Martin mentioned appear in the exhibition

1 John Martin at Tate Britain – full of sound and fury? http://blog.tate.org.uk/

?p=8336

2 ‘Greek’ Thomson, Edinburgh University Press 1994, edited by Gavin Stamp and Sam McKinstry. Stamp writes in his essay ‘Perspectives’: ‘Surely he was at heart, an intense romantic … who brought exotic glamour and immense intellectual distinction to the wet, smokey streets of Glasgow.’ p240.

3 Ibid; in essay ‘On discovering ‘Greek’ Thomson’ by John Summerson, p3.

4 Ibid; as Stamp argues in his essay Perspectives: ‘It would be a grave mistake to interpret Thomson’s admirationfor Martin purely in terms of architectural images which he brought to tectonic reality in the streets of Glasgow. Thomson’s admiration for Martin goes much deeper, for it was the subject matter of the images that surely seized Thomson’s imagination. As well as set pieces of the Old Testament catastrophes, Martin made a series of engravings of Milton’s Paradise Lost and of

the Last Judgement, as well as illustrations for various editions of the Holy Bible. These must have deeply impressed Thomson who was a profoundly religious man and whose theory of architecture was moral and theological.’

5 Post-war Transactions of the Ecclesiological Society, Vol 2, part 2 (1949, pub. 1950). Yearbook includes ‘Rogue Architects of the Victorian Era,’ by HS Goodhart-Rendel.

6 Dodgem Logic launched in 2009 and ran for eight issues. For an insight into Moore’s own brand of Localism, refer to: ‘Think Locally: Fuck “Globally” – Alan Moore on Dodgem Logic’ http://thequietus.com/articles/06607-alan-moore-interview-dodgem-logic The magazine still exists online at www.dodgemlogic.com

The Architects’ Journal Architecture News & Buildings

The Architects’ Journal Architecture News & Buildings

Leave a comment

or a new account to join the discussion.