Stones are mined in Jerusalem to construct a myth of continuity, furthering the colonial erasure of Palestine

The Israeli use of stone to construct a narrative of continuity in Jerusalem is coupled with a deliberate attempt at disrupting the enduring Palestinian presence in the city. Carving Israeli history into Jerusalem’s rocky topography is paralleled with an active process of carving out the city’s Palestinian history. The city’s stones bear witness to this process of colonial erasure. Palestinians in Jerusalem live under the constant threat of forced evictions and house demolitions. Rubble and dust substitute sites where Palestinian livelihoods were once etched into the stone. The material’s debris fills Jerusalem’s streets with shattered memories and interrupted dreams.

Viewing Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives, one is faced with the city’s apparently sculptural feel. Jerusalem’s cobblestones, flying buttresses and vaulted roofs together summon a ubiquitous visual uniformity. Stone is what these elements have in common. However, stone is not merely the substance that grants Jerusalem its aesthetic identity: it is the material that has defined the city’s trajectory since its earliest foundations. Every story of Jerusalem is also a story of its stone.

The Foundation Stone site is considered too sacred for most Jews to enter, and many instead visit the Western Wall, as the holiest place where Jews are permitted to pray

Credit: Yevgenia Gorbulsky / Alamy

Quarried from the hills surrounding the city, as well as from other nearby hills in Palestine’s central highlands, Jerusalem limestone has been the city’s primary building material since antiquity. It is at once the material that carries its structural skeleton and the flesh that grants the cityscape its golden hue. Generations of local stonemasons have long tended to the material’s qualities and varieties; each type of stone has a local name based on its specific texture, tint and malleability. Whether it ends up in the city’s tiniest architectural detail or its grandest monument, every stone is a contribution to the many sediments of matter, and of history, that make up Jerusalem.

In a place like Jerusalem, where the sacred and the mythical are deeply engrained in the city’s history and image, stone’s materiality is no less crucial than its ethereal connotations. Formations of natural rock and human-assembled masonry are not beheld as mere worldly artefacts; they are equally divine links between Earth and the heavens. Whether in the Foundation Stone under the Dome of the Rock, the Stone of Anointing at the entrance of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, or the Western Wall that delineates the Old City’s edge, Jerusalem’s stones carry transcendental virtues that supersede the material’s tangible qualities.

Stone has great significance to Abrahamic religions, and there are many quarries near Jerusalem

Credit: Historic Illustrations / Alamy

While rooted in the city’s long history, Jerusalem’s architectural conformity to stone is a relatively modern construct. In 1917, the first year of British colonial rule in Palestine, Sir Ronald Storrs, the colonial governor of Jerusalem, declared that all new buildings in the city must be faced with local Jerusalem stone. The building law, which is still in effect today, constituted part of a greater colonial urban planning effort in the Holy City. The Pro-Jerusalem Society, established by Storrs a year later, played an instrumental role in the preservation of the Old City and in guiding modern construction outside Jerusalem’s historic walls.

Despite its declared mandate to protect the interests of all Jerusalemites, the Pro-Jerusalem Society primarily served colonial visions for the future of the Holy City. British architect CR Ashbee, who oversaw the society’s preservation schemes, ordered the destruction of buildings that constituted a departure from Jerusalem’s stone cityscape. Arab-owned shops, primarily constructed in tin and timber, were removed to make visible the stone walls of the Old City. In Ashbee’s scheme, maintaining a sanitised image of the Holy City took precedent over the livelihoods of those who resided within it.

‘Palestinian expertise in stone quarrying, cutting, masonry and dressing remains the cornerstone of the country’s construction sector’

Around the same time that these efforts were implemented to preserve the historical character of the Old City in the early 20th century, Jerusalem was expanding at an unprecedented scale beyond its historic boundaries. Modern constructions, including commercial centres, residential developments and public spaces, gave birth to a New City outside the historic centre. The landscape of stone steadily expanded into the hills and valleys surrounding the city, overtaking terrains that were once covered in cultivated estates and olive terraces.

British architectural interventions in the New City saw local stone as a vehicle for their ‘colonial regionalism’, a prevalent design language around the empire. This is most palpable in architect Austen St Barbe Harrison’s projects in Jerusalem, including the High Commissioner’s Residence and the Rockefeller Archeological Museum. Although concrete had been well established in Palestine by that point, Harrison emphasised local stone as both a structural and cladding element. The two stone-covered buildings dominated the hills they stood on, rising like modern-day Crusader castles. A closer look at their architecture, however, reveals another overriding influence: the two buildings’ abstracted geometries and stone-vaulted roofs were directly borrowed from the Palestinian vernacular architecture found across the country’s central highlands.

British architect Austen St Barbe Harrison used stone in the design of the Rockefeller Archaeological Museum to build a colonial architectural language across the empire

Credit: G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection

The Palestinian vernacular was no mere abstract precedent in Harrison’s grand designs in Jerusalem. Harrison understood that his projects could not have been realised without relying on local Palestinian construction knowledge. Like dozens of foreign architects before him, he realised that the intergenerational knowledge of local stonemasons was an indispensable asset for modern architectural construction in Palestine. Today, even with the advent of competing imported building technologies and materials, Palestinian expertise in stone quarrying, cutting, masonry and dressing remains the cornerstone of the country’s construction sector.

The continued eminence of stone in Palestinian architecture did not mean that the nature of its use was unchanging. As stone stretched further into Jerusalem’s expanding cityscape, it began to witness integral modifications in its architectural utility and value. The city’s expansion coincided with the growing use of a composite substance that contested stone’s place as the primary structural material in local construction: concrete. Although stone still covered buildings’ exteriors, it was no longer the skeleton that carried the building’s weight, but a thin layer of cladding that covered it. Concrete took the burden of making buildings stand, while stone wrapped their exteriors with a veil of authenticity.

Ultimately, the Rockefeller Archaeological Museum's form was still influenced by Palestinian vernacular and its realisation relied on local Palestinian construction knowledge. Stonemasons are seen carving out a new capital during renovations to the Temple Mount in the 1940s

Credit: G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection

Realising the persistence of stone’s significance in Palestinian cityscapes, while also accounting for the radical shifts in the material’s use, contemporary Palestinian architects have revisited stone’s potential in today’s architecture. The most conscious response to the future of stone in Palestinian architecture is from the Bethlehem-based studio AAU Anastas. The Anastases condemn what they characterise as the ‘misuse of stone’: the compromising of the material’s structural qualities for its contemporary use as a cladding material. Equally significantly, they warn that the expertise of stone building in Palestine is disappearing due to these contemporary practices.

The problem that the Anastases identify is not particularly new. Stone’s relegation to a cladding material has pervaded architectural thought and practice within Palestine and the Arab region for decades. However, it is their experimental approach towards a workable alternative that is worth noting. In their research project Stone Matters and the Analogy pavilion from 2018, the architects deploy computational simulation and digital fabrication to present an innovative stone vaulting construction technique, opening new possibilities for stone’s structural use and form. Their use of digital technologies does not undermine their attentiveness to the local conditions of the craft. The in situ assemblage of their vaulted stone pavilions is based on a close understanding of the history of Palestinian stereotomy and the craftsmanship at the heart of present-day stone construction in Jerusalem and elsewhere around the country.

On a sloped, triangular site in Jerusalem’s new precinct, the National Library of Israel by Herzog & de Meuron is imagined as a link between two other institutions: the Israel Museum to the south and the Knesset to the east

Credit: Boaz Rottem / Alamy

In some measure, the Anastases’ emphasis on stone’s embeddedness within the Palestinian architectural past and future is a direct response to Israeli attempts at appropriating stone’s long-term trajectory in Palestine to serve their own ideological ends. Since the early days of the foundation of the Israeli state in 1948, numerous Zionist architects have treated stone as an instrument to claim their rootedness in the ‘Promised Land’. From the 1950s onwards, a series of debates ensued within Israeli architectural discourse on the building material that engendered the spirit of the Zionist national-colonial endeavour in Palestine. Tel Aviv’s modernist concrete and Jerusalem’s ancient limestone stood at the two opposite ends of this debate, each representing a particular image and identity of the Israeli state.

Today, Israeli projects in Jerusalem continue to employ local limestone to naturalise their colonial architecture with the city’s historical landscape. Among the latest architectural projects of this sort is the National Library of Israel, designed by the Swiss firm Herzog & de Meuron. Sitting on a hill adjacent to the Israeli Parliament (Knesset), Supreme Court and the Israel Museum, the project is part of a larger Israeli colonial scheme to turn Jerusalem into its de facto capital by locating all state institutions there. Although the architects state the library’s independence from these other institutions, they emphasise the library’s role as a ‘link between the cultural and civic institutions around it’. The library, therefore, is envisioned not as a standalone artefact but as a connecting tissue that stitches these colonial institutions together, further asserting their authority over Jerusalem’s cityscape.

Building on the city’s tradition of stone construction, the Swiss practice uses contemporary construction techniques. A perforated stone facade is attached to a precast concrete structure

Initially commissioned to Israeli architect Rafi Segal, the library’s design was only later transferred to the Swiss practice, following a legal dispute. Segal’s original design envisioned the building as a ‘landscape of stone steps’ that is carved into the site rather than placed on it. Although Herzog & de Meuron’s building replaces the sharp lines of Segal’s proposal with a more curvilinear design, it preserves stone’s status as the bond that ties the building into Jerusalem’s hilly landscape. However, stone’s use in the building is not based on the long trajectory of stonemasonry and craftsmanship in the city, but is a fetishised and reinvented version of this history. In an attempt to construct a continuous thread of Jewish ancient past and present in Jerusalem, the library’s stone facade openings and carvings ‘derive their shapes from a projection of erosions on the ancient stone walls of the Old City’. The solidity and weight of the stone is deployed to more than compensate for the fragility of the exclusive claim of Israel over the city.

Looking again over Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives, the view that at first seemed sculptural now feels less so. Jerusalem appears more like a broken monument: a collection of multiple disjointed artefacts. Its aesthetic unity emerges like a distortion – a concealment of the many layers of architectural camouflage that have been laid on the city over decades of colonial intervention and obliteration. At street level, closer to the ground, where piles of rubble are mixed with stone dust, a more truthful version of the material’s afterlives unfolds. Not a city, but cities, of stone appear before your eyes.

Case studies

Analogy pavilion, Jerusalem, AAU Anastas, 2018

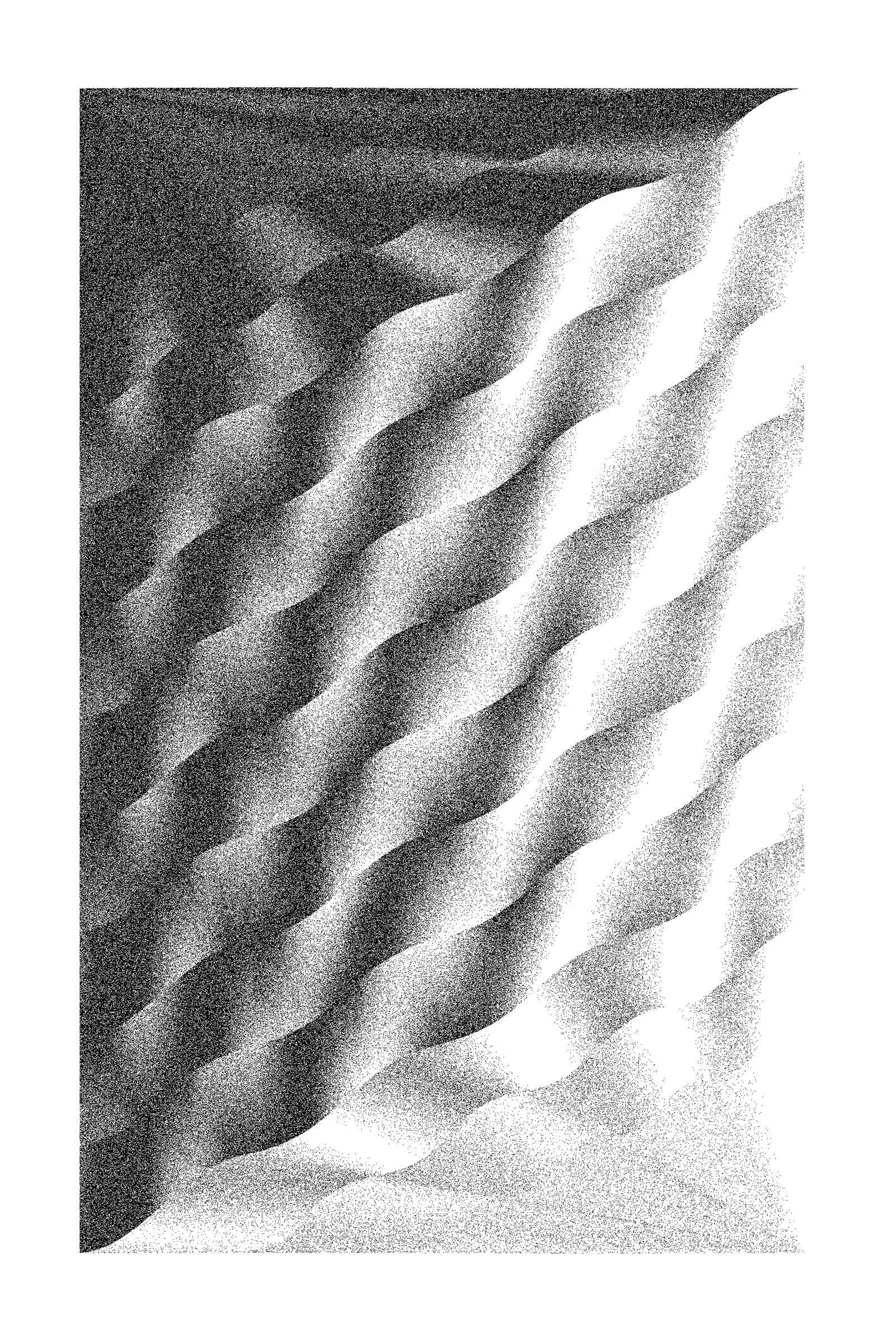

Through experimentation with recurring building components, such as vaults, lintels and columns, AAU Anastas explore novel ways of building with stone. In Jerusalem, where the use of stone is sacred and holds great meaning, they propose a method of construction which stems from Islamic building type ‘aqd takaneh – a 13th-century rectangular, as opposed to square, vaulted structure, which went on to be employed in Renaissance palaces and Palestinian houses during the Ottoman period. Analogy, a project exhibited at Qalandiya International 2018, consists of stone voussoirs assembled to reciprocally support each other and form an undulating surface. Analogy is part of the wider research project Stone Matters, through which AAU Anastas are seeking to develop a new architectural language using stone, respecting modern needs and construction methods while building on ancient techniques. The architects are consciously looking to desacralise the use of stone, particularly in the Palestinian context.

Credit: AAU Anastas / Mikaela Burstowa Burstow

Credit: AAU Anastas

Credit: AAU Anastas / Mikaela Burstowa Burstow

Credit: AAU Anastas

St Mary of Resurrection Abbey extension, Jerusalem, AAU Anastas, 2018

St Mary of the Resurrection Abbey is a comprehensive example of Crusader architecture in Palestine, combining local and imported architectural elements. In 2018, AAU Anastas extended the monastery’s shop with a flat stone vault, stitched into the historic site by the continuity of building material, rather than form. Solid stone columns support the vaulted ceiling made up of 169 interlocking voussoirs. The architects used an ancient technique patented by French engineer Joseph Abeille in 1699: a dry masonry system in which polyhedral stone modules are arranged to alternate and support two adjacent modules, creating a chequerboard pattern. The load is then carried horizontally to the perimeter wall. AAU Anastas adapted this technique, making use of modern structural strength tests and methods of fabrication to create an interlocking structure. Experiments in stereotomy (the art and science of cutting three-dimensional objects into required shapes) play a crucial role in their projects, which rely on complex and precise geometries rather than the use of a binding material.

Credit: AAU Anastas / Mikaela Burstow

Credit: AAU Anastas

Credit: AAU Anastas / Mikaela Burstow

Credit: AAU Anastas

Credit: AAU Anastas / Mikaela Burstow

Lead image: The Dome of the Rock is built over the Foundation Stone, believed to be the place where God created the world and where Abraham attempted to sacrifice his son. Credit: Yevgenia Gorbulsky / Alamy

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design