In his book Twenty Minutes in Manhattan, the late architect Michael Sorkin detailed his morning walk from his Greenwich Village apartment through Washington Square Park to his Tribeca office. For Michael, the simple act of walking was critical to asserting a right to the city and to the formation of a democratic one. It is through walking, he wrote, that we can observe the small changes in our neighborhoods and our neighbors over time and pay attention to the urban struggles that create the cities we know and love. Propinquity — the space of nearness, neighborliness, and kinship — was central to his localist internationalism and to his idea of the good city. It is for this reason that Michael deplored the “architecture of insecurity”: the global proliferation of CCTV cameras, tollway scanners, GPS tags, and gated communities throughout our cities. These practices of control removed the possibility for the collision and collusion of bodies in physical space, the friction so essential to city life.

For Michael, the Israeli occupation of Palestine and its blockade of Gaza were an example of the architecture of insecurity on steroids. The Palestinian Gaza Strip had become a canvas on which Israel developed, tested, and monitored different techniques of suppression. Crammed into a space of 139 square miles, 2 million people have lived under siege for nearly 20 years in one of the most beleaguered urban environments on Earth. While it is frequently described as an “open-air prison,” what this looks and feels like on the ground is a laboratory, precisely engineered to study the science of domination. In Gaza, the Israelis built algorithms to compute and quantify the cost of human life in order to pursue “proportional warfare” and constructed databases to measure the caloric intake of Gaza’s imprisoned population.

In 2014, Operation Protective Edge, the third major Israeli assault on Gaza in six years, brought destruction on an unprecedented scale, killing over 2,100 Palestinians living there. The Harvard scholar Sara Roy, who has studied Gaza for over 30 years, wrote shortly after the 2014 bombardment, “I can say without hesitation that I have never seen the kind of human, physical, and psychological destruction that I see there today.” Michael was outraged by this assault on Gaza. It spurred him to create a framework to think through visions of a shared urban future for both Israelis and Palestinians. For him, at the heart of the conflict was a crisis of propinquity. He saw Israel’s separate and unequal provisioning of systems of water, sanitation, transportation, green space, and other infrastructure to Palestinians as an obvious and violent injustice. His frustration was exacerbated by the fact that, as he had shown long ago in the case of Jerusalem, it was more than possible to plan an efficient and equitable shared city.

Through his New York–based NGO Terreform, which I directed for several years, we brought together a group of designers, environmentalists, planners, activists, and scholars from Palestine, Israel, the U.S., U.K., India, and elsewhere to respond to the brutality of Operation Protective Edge with ideas that look beyond Gaza as a site of bombing and deprivation. The result was a collection of projects and essays gathered together in the book Open Gaza: Architectures of Hope, which I co-edited with Michael. The volume was intended to be part of a traveling exhibition that would end in Gaza and become a platform for further initiatives with Palestinian Gazans to envision a more just — and more beautiful — urban future. But getting the necessary permission from Israel or Egypt to enter Gaza has become increasingly difficult, in particular for researchers and all those who do not work under the banner of “humanitarianism.” As one of the contributors in the book shares, she was forced to use the tunnels dug by Hamas between Egypt and Gaza to visit her family there after it was clear she could not pass through either the southern or northern crossings. In the midst of our planning to travel to Gaza, the world closed down with the onset of the pandemic, and Michael himself was cruelly taken from us by COVID in March 2020. The exhibition never arrived in Gaza or elsewhere, but I ensured Open Gaza made it out into the world in 2021 despite his absence.

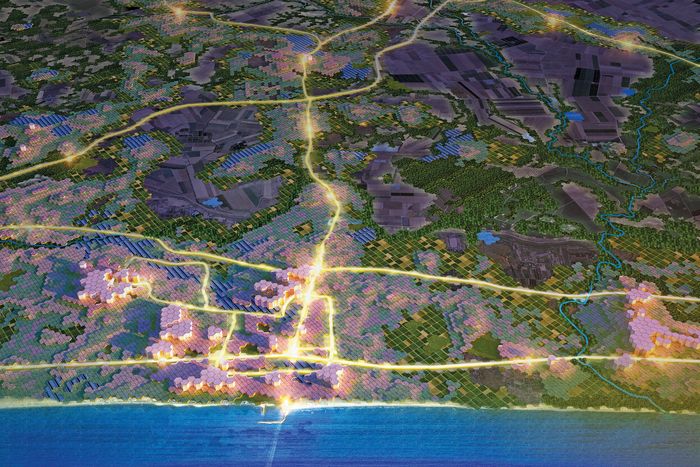

In presenting its plan for a future Gaza, the contributors at Terreform, including Sorkin, admit that it comes out of a wild proposition: “One thinks very differently about Gaza … if its political border disappears as a physical fact.” Terreform’s vision throws off the “arbitrary and cruel” boundaries imposed by partition and occupation to reknit the city back into the region. Its Gaza is a Ring City that embraces its hinterland rather than looking to the sea, where its people and development are concentrated now. Although Palestine is a maritime nation, Terreform chose to look to the hinterland because it offers opportunities to redistribute that density and population growth, increase access to nature, and provide a broader range of living circumstances. A “necklace of settlement” is organized around an agricultural core that also functions as a park. But this does not make it an insular place; the proposal also includes a coastal ferry system that connects Gaza City to Haifa; Izmir in Turkey; Marseille, France; and Tangier, Morocco. It would join a newly constructed heavy rail and an improved roadway system to enable a multimodal system for travel and trade. In this urban design, an Israeli and a Palestinian can wait together for a high-speed ferry on their way to Marseille. This is a Gaza of open streets, public transport, decent affordable housing, and urban farms; structures that can be traversed in 20 minutes and house populations invested in their own neighborliness — a city that has what it needs to integrate with the rest of the world.

Other contributions in Open Gaza also remind us of Gaza’s historic connectivity and its future potential to become a regional hub. It was not so long ago, as the architects Mahdi Sabbagh and Meghan McAllister remind us, that Gaza was a place where coastal routes from Africa to the Middle East and Europe all passed through. In their rhetorical plan, which they call “Timeless Gaza,” they layer the Gaza of the Bronze, Hellenistic, Roman, and medieval Islamic eras, as well as an imagined contemporary period — onto a map, bringing its history as a hub of trade and exchange into the foreground. The historic port, the temple of Marnas (the Gazan god of rain and grain), along with a downtown, sprawling suburbs, a sports stadium and an airport, constitute the urban form of a timeless Gaza. Palestine can once again be a place of connection, they assert.

At the ground level, making time and space for contemplation is also necessary. The architect Romi Khosla proposes a Nakba memorial to be placed in Gaza as a place of dialogue and reconciliation. The Nakba (meaning “catastrophe” in Arabic) refers to the moment in 1948 when the newly established Israeli forces launched a major offensive and an estimated 700,000 Palestinians — a majority of the prewar population — were expelled. To this day, the Nakba anniversary is a reminder of the events of 1948 and of the ongoing injustice suffered by Palestinians. However, the memorial by Khosla is not just for Palestinians; it aims to foster propinquity, a public space for interaction between Israelis and Palestinians. It does this first by entirely replicating Berlin’s Holocaust monument in Gaza. This concrete-slab landscape, originally designed by Peter Eisenman and Buro Happold, would take on an additional meaning in Gaza, allowing a space of remembrance for both the Holocaust and the Nakba. Khosla’s design inserts within that landscape a pit of contemplation, which is modeled on the Hand of Justice pit designed by Le Corbusier in Chandigarh, in north India. Like the one there, this pit is designed for communities in disagreement with each other, in the spirit of Le Corbusier’s idea that “there are always two sides to every question.” Khosla adds that here, Israelis and Palestinians would not “magically” pretend the inequalities had vanished, but agree to certain basic principles and negotiate new agreements.

The reality that Gaza faces today could not be further from this shared and open future. The impact of the Israeli blockade and its infrastructural de-development on Gaza has been calamitous. The crisis of propinquity is stark. In Open Gaza, Tareq Baconi, author of the book Hamas Contained, recounts how Palestinian Gazan society had started to turn in on itself. “Extreme poverty, hunger, loss of dignity, grief, and claustrophobia are all fundamentally restructuring the tenets of humanity in this place,” Baconi explains. He recalls how, in the aftermath of Operation Protective Edge, he went to a school where the little boys told him that they had lost half of their classmates that summer. Gaza is, Baconi writes, “the clearest spatial manifestation of what absolute domination looks like.”

The current moment of extreme crisis demonstrates this even more starkly. After Hamas militants launched an indiscriminate attack on October 7 that killed an estimated 1,300 Israelis, the Israeli response has been predictably ferocious, murderous, and equally indiscriminate. Over just six days, Israel has dropped 6,000 bombs onto Gaza and cut off fuel, electricity, water, food, and medical supplies. It has called on over 1 million Palestinians to evacuate the northern half of Gaza, while continuing to bombard the strip. The current conflict is not a humanitarian emergency, however, but a political one, grounded in a failure to see a common humanity — again, a crisis of propinquity. Few in occupied Palestine raised their voices against Hamas’s brutal and unjustified killings of civilians in Israel; Israelis have not been able to see Palestinians as human beings. Many scholars of genocide and ethnic cleansing warn that the language used by Israeli political and military figures “appears to reproduce rhetoric associated with incitement to genocide,” including Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant declaring on October 9 that “we are fighting human animals and we act accordingly … You wanted hell, you will get hell.”

How can deeply unjust contexts become sites where those who are excluded restore their sense of collective capacity? This is what Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman, architects and University of California professors, ask in their contribution to Open Gaza. Based on their work on border areas across the world, specifically the U.S.–Mexico border, they suggest a pragmatic, incremental approach to strengthen the sense of interdependence between people on opposing sides of a struggle. More concretely they propose the establishment of Cross-Border Community Stations in Israel and Palestine. They created such stations in impoverished communities on both sides of the border in San Diego and Tijuana where residents could discuss issues both sides had in common, like illegal trash dumping, air pollution, and affordable housing. The hardening of the border wall and the subsequent difficulty of crossing it meant they also had to rely on a telecommunications platform to facilitate these cross-border dialogues. Cruz and Forman argue that community stations on both sides of the border between Gaza and Israel would similarly increase the possibility of interaction and mutual recognition between Palestinians and Israelis. This work is not meant to distract from the call to end the Israeli occupation, of course, but to build, on a human-to-human level, a foundation for both communities to practice planning for a more shared future.

Reflecting on Open Gaza now, the impetus to see Palestinians in Gaza as a source of life, capability, and possibility rather than as grim statistics has never been more urgent or important. Palestinians must be granted self-determination — control over the social, political, and economic resources that frame their own lives. But is Israel able to live side by side with Palestinians who are neither occupied nor made to be dependent on humanitarian aid? Will Palestinians ever be allowed to walk through their cities to ponder the incremental changes happening in their neighborhoods and negotiate with their neighbors to create the city they want, rather than just survey the ruins of their past and present? This might seem impossibly distant in the present moment, but the only way forward is premised on the equal rights of Palestinians and Israelis. It is beyond time for Israel to end the occupation and reconsider a new politics of closeness.