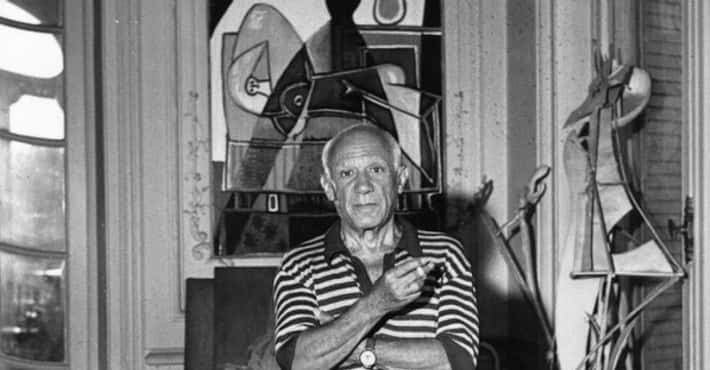

Every Hidden Symbol In Picasso's Guernica

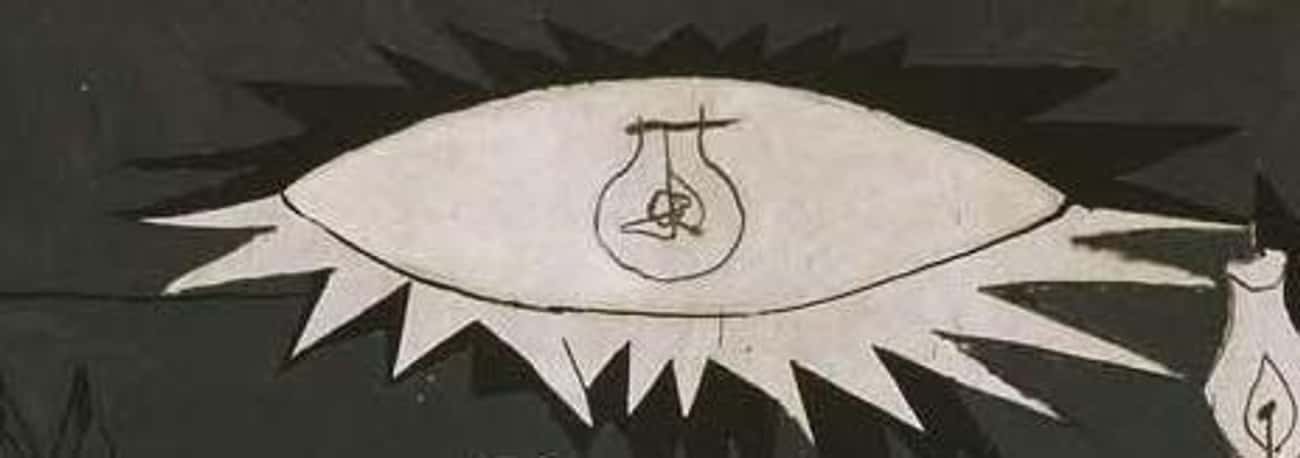

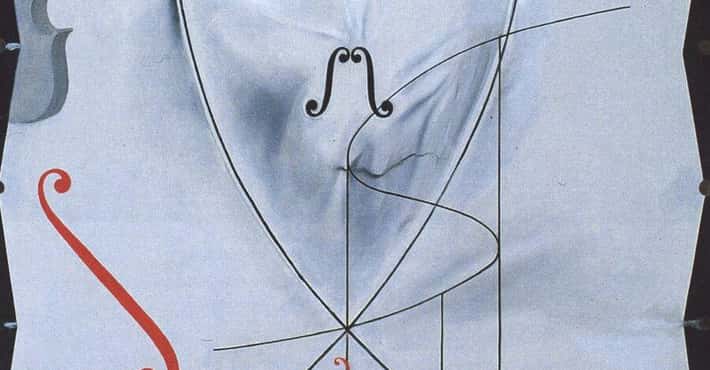

The Sun Is A Technologically Advanced Eye

One of many multifaceted symbols in the work, the combination eye/light bulb in the upper section suggests everything from the watchful eye of God to the vengeful gaze of Franco bearing witness to the aftermath of his orders. That the strike on Guernica was in part carried out as a means to test new artillery and blitzkrieg tactics resonates on a linguistic level; the Spanish for bulb (bombilla) is quite close to the Spanish word bomba.

One possible interpretation is that the light bulb/eye is a nod to new technology being used for nefarious purposes. Light as a symbol of creation goes back to the Book of Genesis, when God creates the Earth out of formless darkness with the words, "Let there be light." In Guernica, the light illuminates destruction rather than creation. Given the light bulb/eye's God-like presence in the scene, it may serve to illuminate the devastating capabilities of modern technology.

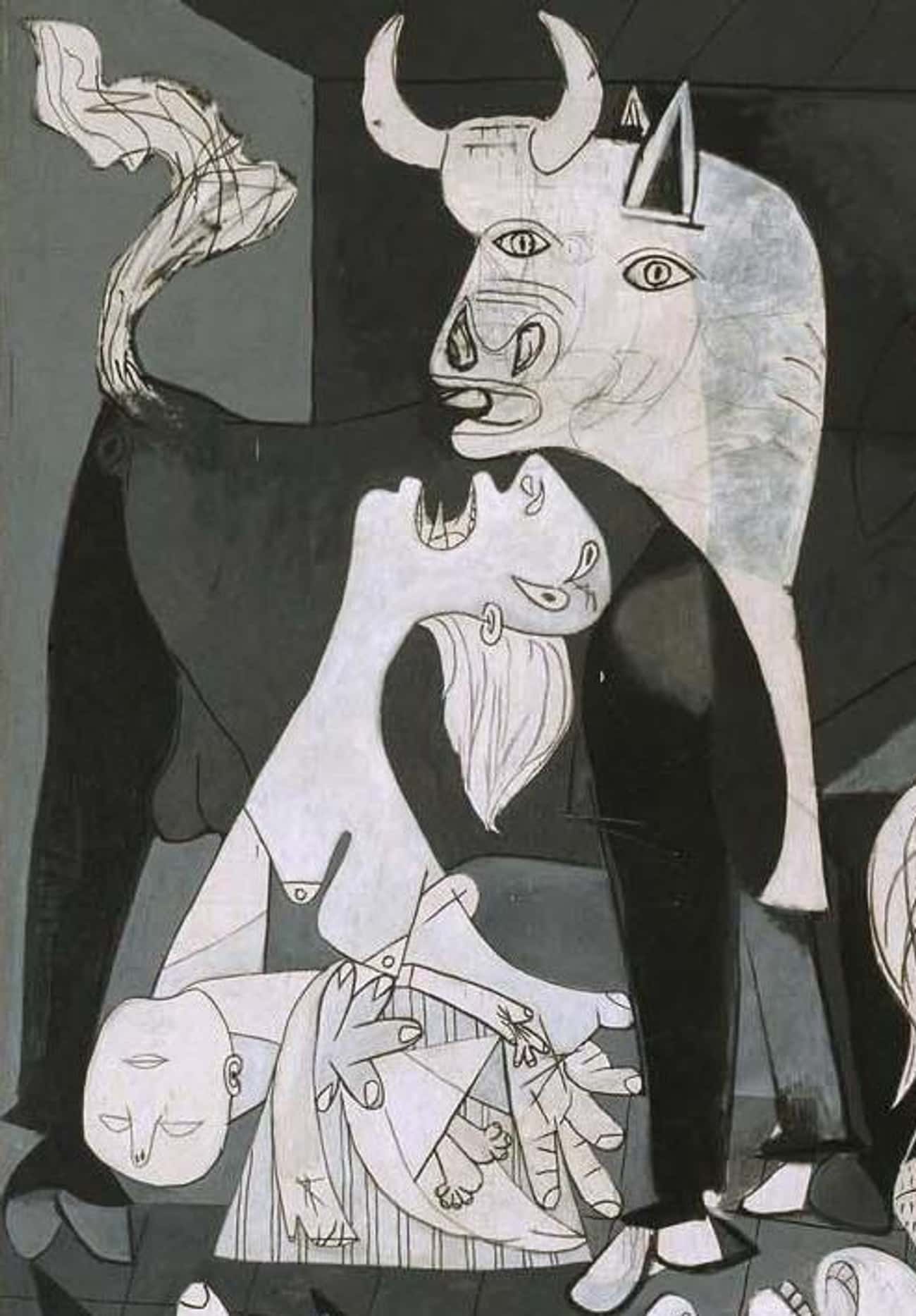

The Mother Cradling Her Fallen Child Evokes Early Christian Imagery

On the far left of the painting, Picasso included one of the most recognizable forms from Western art - the anguished mother cradling her lifeless child, mirroring the pietà. Some of the most famous versions of the pietà are religious works by Titian and Michelangelo that display Christ’s mother Mary holding Jesus in the moments after his body was removed from the cross.

Picasso’s pietà secularizes Mary’s anguish by trading her loss for a Guernican mother’s.

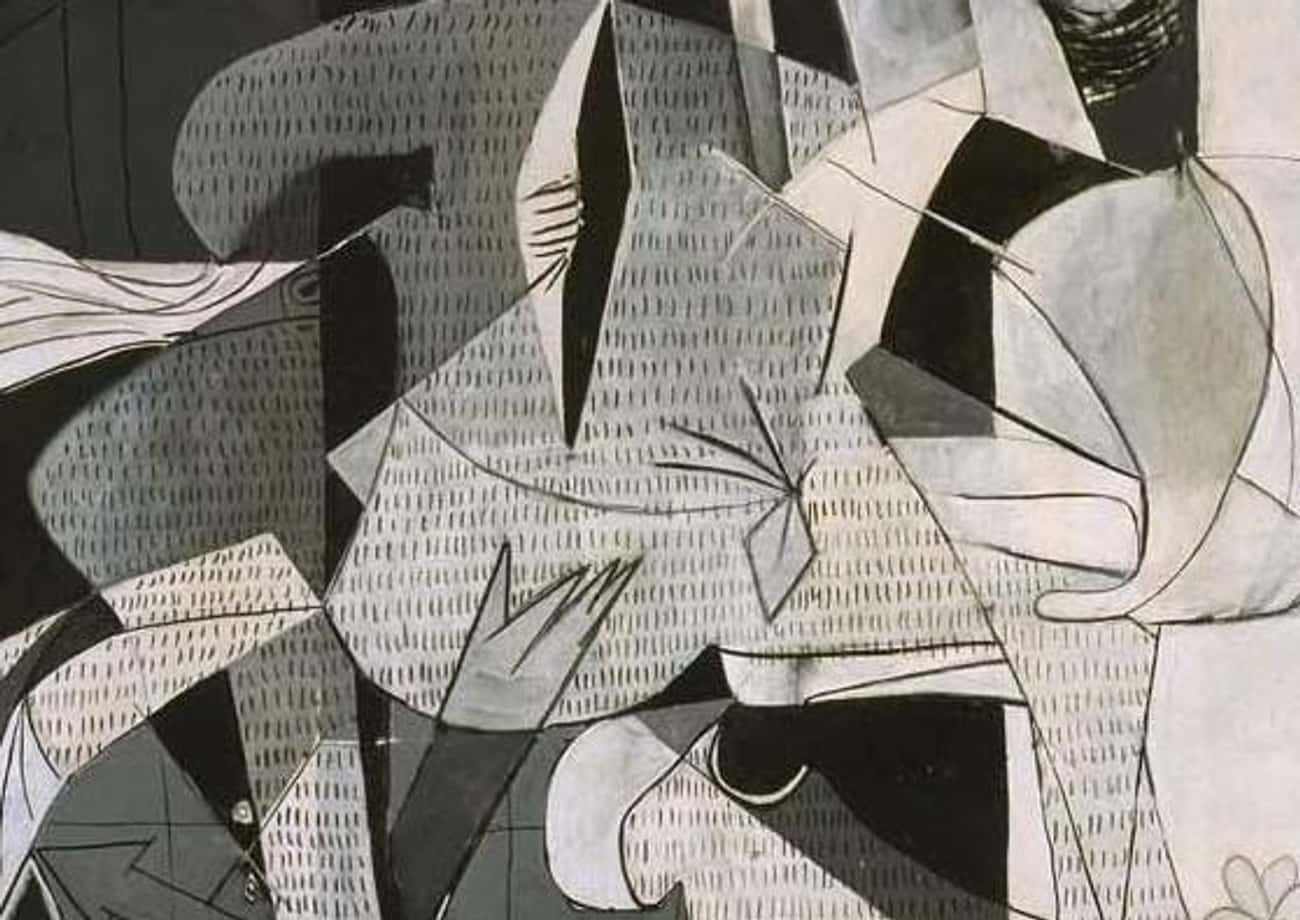

Picasso's Black And White Color Scheme Is An Homage To Newspapers

While Picasso didn’t incorporate any actual newspaper into the composition itself, his stylized black and white palette coupled with the near-typographical hash mark patterning evokes the medium. Picasso first heard the news of the Guernica air raid and its aftermath via a newspaper article, which included black and white photos of the event.

Further, the invocation of reportage helps establish the painting as a document bearing objective witness to the citizens’ tragedy.

The Bull May Signify Fascism

When the poet Juan Larrea first spoke to Picasso about Guernica and suggested it as subject matter for a painting, Picasso claimed he had no idea what city looked like after such an event. Larrea said it looked like "a bull in a China shop, run amok." The bull in question, in the case of Guernica, may have been Franco and the imposing force of the fascist state. It’s also widely reported that Picasso himself thought of the bull as representing brutality and darkness, a further testament to the interpretation of it as a figure representing fascism.

The meaning is somewhat marred and open to multiple interpretations. Picasso often said his choice of images happened instinctively and without specific intent. He even stated, in regards to questions about symbolism, "A bull is a bull and a horse is a horse."

In other work, Picasso frequently drew himself as a Minotaur, the mythological half-man/half-bull. The bull may represent something more personal to Picasso, such as his own reaction to the event. Given Minotaurs frequently carry out acts of aggression in his work, the nod to the mythic animal may be another indication it represents the terrors of fascism.

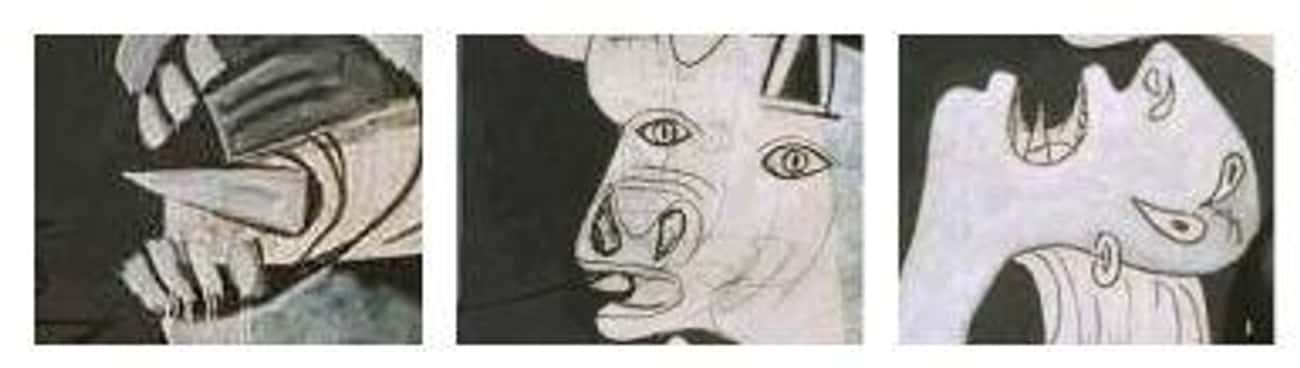

The Terrified Horse Is The Guernican People

The single largest figure of the entire composition is the horse, which also stands at the center of the painting. Picasso had his own interpretation of the figure, suggesting it represented pain and loss while invoking the four horses of the biblical apocalypse. Like all symbols in the painting, however, there are multiple possible meetings.

Horses are frequently seen as companions during wartime given their use in combat, meaning the horse could signify the people of Guernica struggling to defend themselves. Despite the horse's obvious anguish, its head remains upward and struggling to live. This could point to the endurance of the people and the continuing fight against fascism.

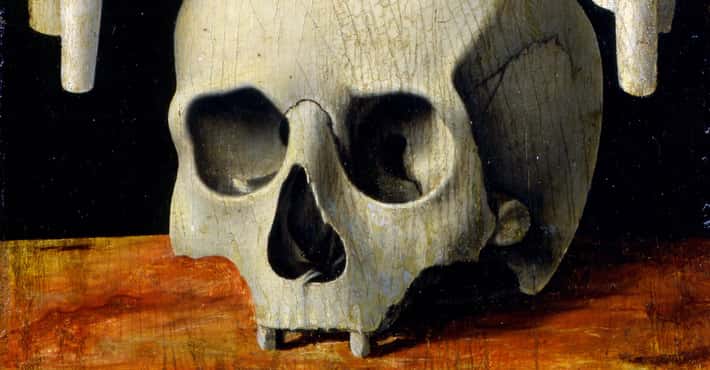

The Horse Hides The Image Of A Skull

If you look closely at the horse's nostrils and teeth, you can make out the image of a human skull. Like all images in Guernica, this can be interpreted in a variety of ways. The skull could be another representation of the suffering of the people and, of course, highlights the amount of loss and destruction that played out that day.

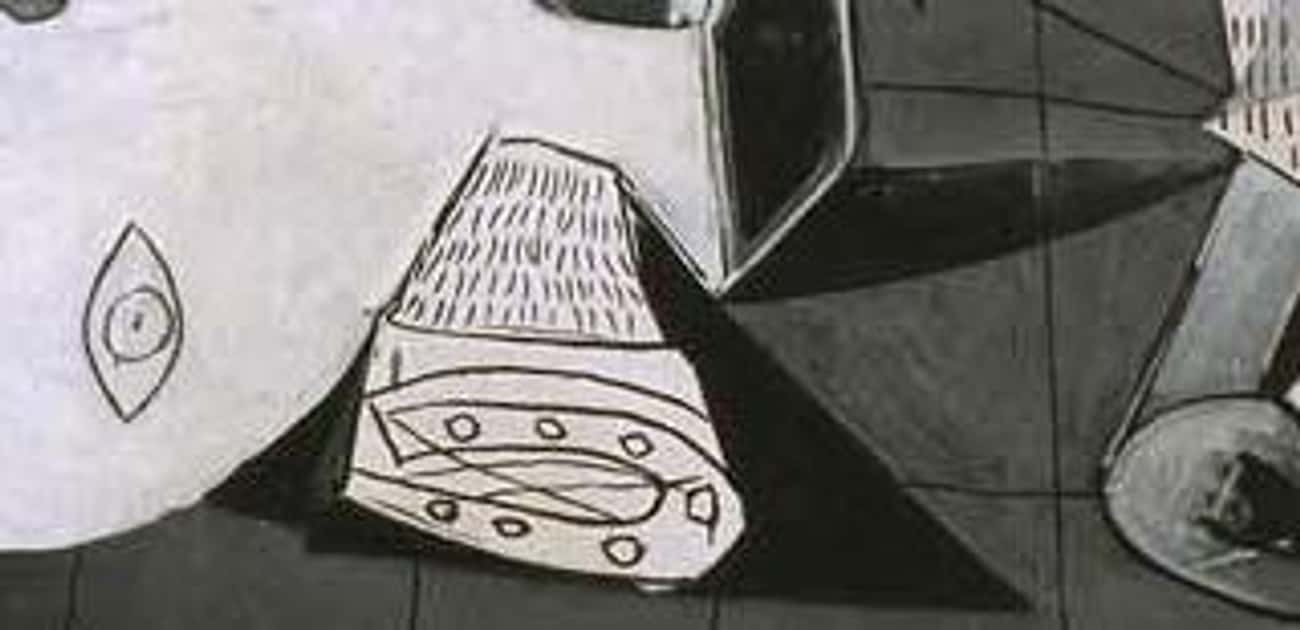

The Dismembered Soldier Represents Both Futility And Hope

Near the bottom of the painting is the dismembered body of a soldier with only his head and arms completely visible. This is yet another example of the human toll of the event. In one hand, the soldier cradles a broken sword and a flower.

The sword may represent the inability of the citizens of Guernica to fight back against modern combat technology. The flower, shrouded in light, could signify hope despite the chaos.

There Are Harlequins Sprinkled Throughout The Painting

Picasso was more than willing to work his trademark motifs into Guernica. He managed to work harlequin figures into the composition that can be quite difficult to notice. The harlequins are mostly hidden beneath the surface of the painting, lying behind other images. The largest is found at the center and sheds a diamond-like tear. The others can be best glimpsed when the painting is viewed from an angle.

A possible homage to his earlier work, harlequins are also associated with the underworld in a mythological sense, which may again signify loss of life and destruction.

Every Tongue Is A Knife

Of the three figures in the composition bearing their tongues - the horse, the anguished mother, and the bull - none have a rounded tongue. The tongues instead come to a dagger-like point. This is another example of otherwise normal figures sharpened by the horrors of Franco’s atrocious act.

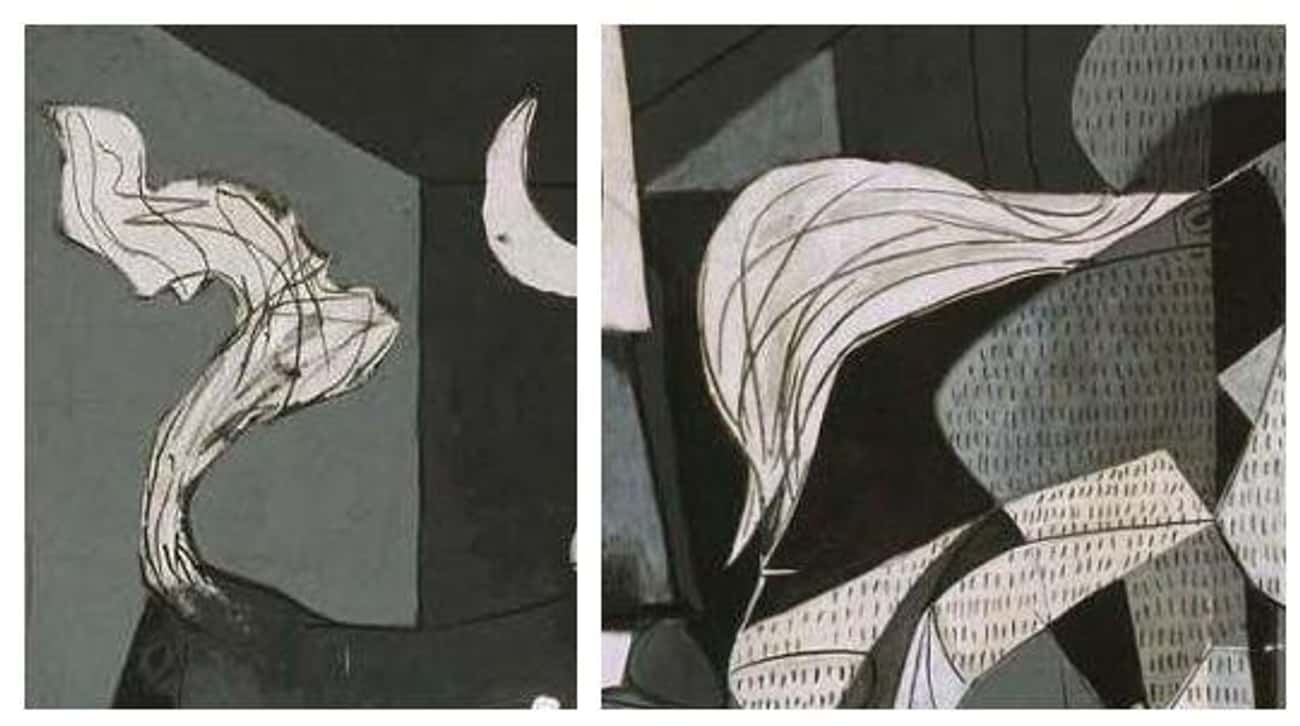

The Dove Symbolizes The End Of Peace

Though it’s mostly obscured by darkness and much smaller than other images, the dove is another of Picasso’s multifaceted symbols. As birds go, few are as loaded as the dove, which is generally employed as a representation of peace. Picasso’s version, with its pained expression and broken body, suggests the destruction of peace.

Its small gash of light, offset by its mostly smoky black nature, suggests the presence of good and bad intentions during combat.

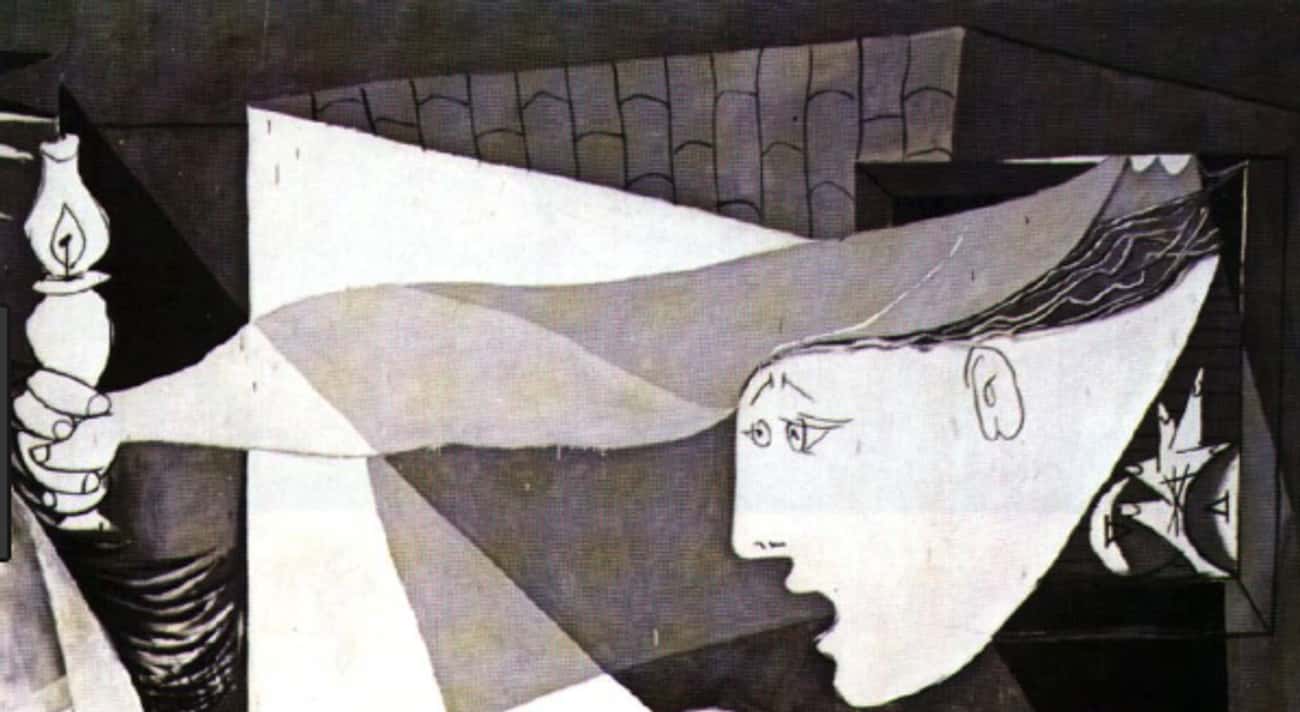

The Woman Holding The Kerosene Lamp Represents Soviet Russia

If you look closely at the woman holding the lamp, you can see a five-pronged symbol next to a crescent shape in the window near her. This signifies the Communist star, sickle, and hammer. This image was displayed on the Soviet Union's flag, meaning the woman clutching the lamp may represent Russia.

An enemy to Germany at the time, Russia could be seen as a possible ally to the people of Guernica.

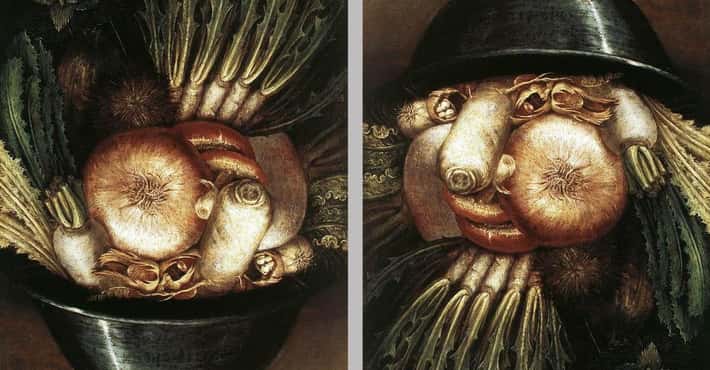

The Horse's Leg Hides A Bull

Yet another figure made from fragments, you can see another bull's head in the leg of the horse. By positioning it below the horse’s belly with its horns thrusting upwards, Picasso suggests bullfighting, which had erotic as well as aggressive associations. By referencing a sport tied up with Spanish history, masculinity, and intimacy in the loss-plagued composition, Picasso plays with its implications and allows for multiple interpretations.

Given the bull could represent fascism and the horse could represent the citizens of Guernica, however, the image could be seen as the fascist regime harming the people.

The Trio Of Women Has Many Possible Meanings

The trio of tightly grouped women on the right side of the painting offers a multitude of possible readings. They could represent the three fates of Greek and Roman mythology, who controlled life. Given the presence of the torch in one of their hands, it may be a nod to Liberty Leading the People. The three martyred virgins of early Christianity is another possible interpretation.

There is also a more personal possibility though. The three women may reference Picasso’s particular stake in resisting Franco. His own mother and sister still lived in Barcelona during his weeks painting the work, putting them at risk if another Guernica-like strike occurred. At the time, Picasso was also involved with three different women, so the figures in the painting may represent the conflicts between his wife and two lovers.

The Horseshoe Recalls Spain's Islamic History

Positioned dangerously close to the dismembered soldier’s head, the crescent shape of the horseshoe is suggestive. It looks like the sacred crescent, a symbol of Islam. Picasso may have been invoking his fear of a potential invasion of Moroccan troops in the region as Islam was the state's predominant religion.

The Smoldering Animal Tails Recall The Charred Rubble Of The City

The tails of both the visible bull and the horse resemble rising plumes of smoke, a conscious evocation of the burned-out state the town was left in following Franco’s campaign.