There’s an image of Jean-Michel Basquiat on the cover of the New York Times magazine from 1985. The photo is by Lizzie Himmel; the headline New Art, New Money. The artist, wearing a dark Giorgio Armani suit, white shirt and tie, leans back in a chair, one bare foot on the floor, the other up on a chair. The combination of the suit and the bare feet is typical of the way Basquiat defined his own image; always with an unconventional bent.

I’ve obsessed over his style when standing in front of Hollywood Africans, a 1983 work from a series where the images relate to stereotypes of African Americans in the entertainment business. It is a banger of a painting and will form part of Basquiat: Boom for Real, a retrospective opening at the Barbican in London this month.

I have a longstanding interest in the way artists dress, from Picasso to Hockney, Georgia O’Keeffe to Robert Rauschenberg, and I think their wardrobes exert as powerful an influence on mainstream fashion as those of any rock or Hollywood stars. These artists carved out instantly recognisable uniforms: clothes that symbolise the same singular point of view as their greatest works, usually with the sense of complete ease that is the holy grail of true style.

Basquiat’s wardrobe was distinctive, whether he was in mismatched blazer and trousers with striped shirt and clashing tie, or patterned shirt with a leather jacket pushed off his shoulders. He was perhaps most recognisable in his paint-splattered Armani suits. “I loved the fact that he chose to wear Armani. And loved even more that he painted in my suits,” Giorgio Armani says. “I design clothes to be worn, for people to live in, and he certainly did!”

In many ways, this bricolage approach to clothing is akin to the way he created his art. “His work was a mysterious combination of elements – text and colour, historical reference, abstraction and figurative techniques,” Armani says. “In his life, he also mashed up creative activities – he was a graffiti artist, a musician, an actor, a maker of great artworks. This eclecticism made him a mysterious and unconventional man. That mix made him stand out.”

Born in Brooklyn, Basquiat and classmate Al Diaz graffitied statements across New York as SAMO© in the late 70s, before he went on to become one of the biggest stars of the 80s art scene with his unique and brilliantly chaotic paintings. He died in 1988 at just 27, but is still regarded as one of the most influential painters of his generation. A painting from 1982, Untitled, sold this year for £85m, putting him in a unique club alongside the likes of Picasso in terms of record-breaking sales.

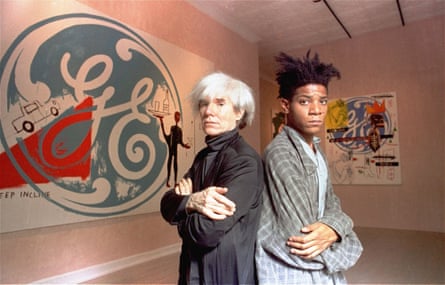

“He was an incredibly stylish artist,” says Barbican curator Eleanor Nairne. “He was very playful about the performative aspects of identity.” He was also aware of the “renewed fixation on celebrity” that coincided with the art boom of the 80s, particularly in New York. He famously appeared in Blondie’s Rapture video, dated Madonna and befriended Andy Warhol.

Cathleen McGuigan, who wrote that 1985 New York Times feature, recounts Basquiat at the hip Manhattan hangout Mr Chow’s, drinking kir royal and chatting to Keith Haring while Warhol dined with Nick Rhodes of Duran Duran nearby. “He attracted the attention of Warhol and Bowie, so was endorsed by those who had already achieved that rare style-icon status,” Armani says. “And he had a very unique look – he had hair as distinctive as Warhol’s and wore suits in a way as stylish and relaxed as Bowie.”

Basquiat’s interest in clothing was not just something he explored or exploited at the height of his fame. In Basquiat: A Quick Killing In Art, by Phoebe Hoban, clothes are an important part of his life story. His mother had at one point designed them, while one of his teachers noted he had pencils sticking out of his hair from an early age. Soon after he killed off SAMO© he was painting sweatshirts, lab coats and jumpsuits for Patricia Field, who gave him one of his first shows at her East Eighth Street boutique. Descriptions of his stirring appearance include this by American curator Diego Cortez: “I remember on the dancefloor seeing this black kid with a blond Mohawk. He had nothing to do with black culture. He was this Kraftwerkian technocreature … He looked like a Bowery bum and a fashion model at the same time.”

Basquiat went on to model in a 1987 Comme des Garçons show wearing a pale blue suit, black buckle sandals, white shirt and white bow tie. Robert Johnston, style director at British GQ, describes Basquiat’s style as “a work of art in itself” and adds: “While meaning no disrespect to his talent, it is hard to imagine he would have taken New York so much by storm if he’d looked more like Francis Bacon.”

Basquiat’s influence on menswear is still felt today. While other icons have referenced his style – Kanye West sported a T-shirt bearing his portrait, Frank Ocean namechecked him in lyrics by Jay-Z, who dressed as him for a Halloween party – there is a more direct effect on fashion. There have been collaborations, via his estate, with the likes of Reebok and Supreme. There’s a photo of Basquiat wearing an Adidas T-shirt with a pinstripe suit which is a template for how the younger generation approach the idea of tailoring. At the S/S 18 shows in Milan, wonky ties with suiting at Marni made me jot down “Basquiat” in my notebook. And with the Barbican show his influence will spread. “The way Basquiat mixed classic tailoring with a downtown nonchalance fits the mood in menswear,” says Jason Hughes, fashion editor of Wallpaper*. “A refined suit worn with an unironed shirt, skewwhiff tie and beaten-up sneakers. The fact that he painted in those suits feels slightly anarchic and nonconformist. I want to wear a suit like that.”

This article appears in the autumn/winter 2017 edition of The Fashion, the Guardian and the Observer’s biannual fashion supplement