What caused the tsunami?

The most powerful earthquake recorded in Japanese history, magnitude 8.9. The tremors were the result of a violent uplift of the sea floor 80 miles off the coast of Sendai, where the Pacific tectonic plate slides beneath the plate Japan sits on. Tens of miles of crust ruptured along the trench where the tectonic plates meet. The earthquake occurred at the relatively shallow depth of 15 miles, meaning much of its energy was released at the seafloor.

How does the earthquake compare with others?

This was the sixth largest earthquake in the world since 1900, when seismological records began. The most devastating earthquake to strike Japan was in 1923, when a magnitude 7.9 tremor devastated Tokyo and Yokohama and killed an estimated 142,800 people. The Kobe earthquake in 1995 was a magnitude 6.9 and caused more than 5,000 deaths and injured 36,000 others. The earthquake that wrecked Christchurch in New Zealand last month was a magnitude 6.3 event. Around 30 times more energy is released as the magnitude of an earthquake increases one unit, for example from magnitude 8 to 9.

Why is the area so prone to earthquakes?

The Pacific plate moves fast in tectonic terms, at a rate of 9cm (3.5 inches) a year. This leads to the rapid buildup of huge amounts of energy. As the Pacific plate moves down, it sticks to the overhead plate and pulls it down too. Eventually, the join breaks, causing the seafloor to spring upwards several metres. The plate tectonics of the region are complex, and geologists are not sure which plate Japan sits on. Candidates include the Eurasian plate, the North American plate, the Okhotsk plate, and the Honshu microplate.

How big were the waves?

The largest waves measured by instruments in the water were 7 metres (nearly 23ft) high in the north-east of Japan, according to the Pacific Tsunami Warning Centre (PTWC) in Hawaii. Other estimates put the wave height at 10 metres. Waves reached 4 metres around the coast of Japan. As the tsunami spread across the Pacific, the wave height dropped to around 40cm in Guam and the nearby Marianas. The most powerful waves appeared to be moving south-west from Japan. Some countries may experience waves up to 2 metres, according to PTWC forecasts.

How much damage has been caused?

Japan has invested heavily in coastal protection and buildings that can withstand tremors. Nevertheless, ports were pounded by the tsunami and the airport in Sendai was inundated. Nuclear power plants were shut down across the country and a state of emergency declared at the Fukushima nuclear power plant, where a cooling system failed. Modern buildings in Japan are designed to absorb the violent sideways shaking that can devastate cities. High-rise buildings can still be damaged, but are more likely to remain standing. There are concerns for low-lying islands in the Pacific.

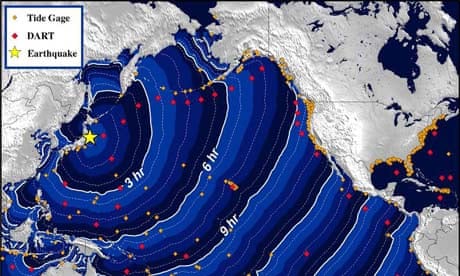

How long will the waves take to reach other countries?

The tsunami moves across the Pacific at a speed of 500mph, with waves expected to reach the island of Fiji and Cairns in Australia at 3.28pm GMT. From then, waves are due to reach Acapulco in Mexico at 7.59pm, Chile at 10.55pm, Ecuador at 11.31pm, Colombia at 11.47 and Peru at 12.33am.

Will there be aftershocks?

Regular aftershocks have already hit Japan as the Earth's crust continues to rupture along the Japan trench. Those tremors are expected to be weaker and are less likely to produce another tsunami. The release of energy along the subduction zone between the Pacific and North Atlantic plates will transfer stress to other parts of the faultline, which could easily generate more earthquakes in the region in coming months.